Scroll to:

DEPDC5 mutations in familial epilepsy syndrome: genetic insights and therapeutic approaches

https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2024.193

Abstract

Background. DEPDC5 (disheveled, Egl-10 and pleckstrin domain-containing protein 5) familial epilepsy syndrome is a group of epilepsy disorders caused by mutations in DEPDC5 gene, which is a part of the gap activity towards rag 1 (GATOR1) complex involved in regulating the mechanism target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. These mutations lead to hyperactivation of the mTOR pathway, disrupting the shaping of neurons and resulting in increased excitatory transmission and the development of epilepsy. The incidence and prevalence of DEPDC5 familial epilepsy syndrome are not well established, but studies suggest it may account for up to 10% of familial focal epilepsy cases. Genetic testing, electroencephalography (EEG), and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are important in diagnosing the disorder, although normal MRI results are common.

Objective: to explain the rare sporadic mutation in DEPDC5 gene with p.R389H, a variant of unknown significance.

Case report. A 6-year-old South-Asian girl was born at 34-weeks from non-consanguineous marriage without any prenatal events. She had hyperbilirubinemia by week-1, which was successfully treated with phototherapy. Her initial seizure occurred when she was three months old, just 2 days after the fever from the vaccination had subsided. It was considered a simple-febrile seizure and no treatment was given. At 3.5-months, she started having recurrent seizures. Workup including MRI/ infectious/metabolic panel was non-conclusive. EEG during the initial presentation showed epileptiform activity from the left temporal region. Despite being on multiple anti-epileptic drugs, the child was diagnosed with refractory epilepsy. Subsequently, EEG at 2.5-years showed inter-ictal bi-hemispheric epileptiform activity. EEG at 5-years showed inter-ictal spikes and wave discharges from bilateral fronto-temporal region with secondary generalization. By 3-years, MRI showed mildly deformed corpus callosum with inadequate thickening of splenium. DNA analysis confirmed heterozygous missense mutation in exon 16 of DEPDC5 gene, without chromosomal abnormalities. Mother was heterozygous for the same mutation but no mutations in the father was found. The child has grossly delayed milestones. Corrected age is approximately 1-year for fine motor and language, 1.5-years for gross motor, 2.5-years for cognition, social skills. She had developed autistic features as well with significant impaired auditory/visual processing. She had hypotonia (Right>Left), wide-based gait, and extrapyramidal movements.

Conclusion. DEPDC5 gene mutation results in amino acid substitution of Histidine for Arginine at codon 389. This mutation has shown to be inherited in familial pattern. This R389H variant is not present in the 1000 genomes database and is predicted to be benign. However, It rather appears to be a sporadic mutation, which is a very rarely observed phenomena. Such patients may respond well to mTOR inhibitors such as rapamycin, making prompt diagnosis and treatment crucial.

Keywords

For citations:

Diallo M.K., Mukesh S., Kapil L., Singla R., Tar D., Tammineedi S.N., Singer E., Chhayani H., Arumaithurai K., Patel U.K., Arora R. DEPDC5 mutations in familial epilepsy syndrome: genetic insights and therapeutic approaches. Epilepsy and paroxysmal conditions. 2024;16(4):338-348. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2024.193

INTRODUCTION / ВВЕДЕНИЕ

DEPDC5 (disheveled, Egl-10 and pleckstrin domain-containing protein 5) familial epilepsy syndrome is a group of epilepsy disorders caused by the activation of the mechanism target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. It is associated with mutations in the recently discovered DEPDC5 gene, which is a part of the gap activity towards rag 1 (GATOR1) complex responsible for regulating mTOR signaling [1]. The mTOR pathway is vital for cellular growth and proliferation, particularly in the brain, where it contributes to neuronal differentiation, synaptogenesis, and dendrite formation, shaping the complex structure of the cerebral cortex [2]. DEPDC5 encodes an inhibitory component of mTOR, and mutations in DEPDC5 result in the hyper activation of mTOR, contributing to the development of the syndrome [1]. This syndrome manifests in various seizure types, including focal seizures, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, SUDEP, and myoclonic seizures [3].

It is worth noting that DEPDC5 variants have been detected in approximately 20% of patients with different brain lesions, making it challenging to differentiate between pathological brain conditions and normal brain structure [4].

Brain imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electroencephalography (EEG) and genetics have played a crucial role in not only identifying brain lesions but also in diagnosing them. Long-term EEG monitoring reveals progressive features of epileptic encephalopathy associated with DEPDC5 mutations, including increasing frequency of multifocal discharges originating from multiple regions in either hemisphere [2]. Individuals with DEPDC5 mutations exhibit distinct EEG patterns, such as stronger theta oscillations and pronounced gamma oscillations, indicating increased cortical excitability and hyperactive mTOR signaling [5]. Brain MRI scans often show bilateral polymicrogyria, macrocephaly, and abnormalities in the corpus callosum, pons, and basal ganglia. However, normal MRI results are also common [1].

The clinical significance of missense or splice-region variants in DEPDC5 is not fully understood, the incomplete penetration of variants adds to the challenge of interpreting these mutations clinically [2]. Despite advancements in genetic testing, brain MRI, and EEG, some cases of this familial epilepsy syndrome remain idiopathic [6]. Additionally, certain patients do not respond to treatment [7]. Therefore, further research is necessary to understand the harmful effects of DEPDC5 gene mutations and improve the clinical interpretation and therapeutic of this condition.

CASE REPORT / КЛИНИЧЕСКИЙ СЛУЧАЙ

A 6-year-old South-Asian girl was born at 34 weeks from non-consanguineous marriage without any prenatal events. She had hyperbilirubinemia by week 1, which was successfully treated with phototherapy.

History of disease / Анамнез

The patient had first seizure episode at 3 months, 2 days after “vaccination fever” subsided. It was considered a simple-febrile seizure and no treatment was given. At 3.5 months, she started having recurrent seizures. Workup including MRI/infectious/metabolic panel was non-conclusive. Despite being on multiple anti-epileptic drugs (levetiracetam, valproate, phenobarbital and biotin) she has refractory epilepsy.

By 10 months of age, she was able to hold her neck and turn prone, fixate her eyes on objects occasionally, and turn her neck in response to auditory stimuli from both sides. However, her tonic labyrinthine reflex and neck righting reactions still persisted, indicating a delay in the development of cortical reflexes. Consequently, the patient was unable to maintain a sitting position and could only sit up from a supine or prone position, lacking the ability to bear weight. Moreover, she exhibited a lack of basic exploratory play and struggled to maintain eye contact with her family and others. The dynamic sitting and static balance were notably poor. Additionally, at 10 months, the child could not consume mashed food, showed fear towards simple sounds, and struggled with sitting and holding objects. Her tongue, lip, and jaw movements were impaired, resulting in an inability to suck or blow. Furthermore, she engaged in stereotypic behaviors such as rocking her head and body while sitting and flexing her head and trunk forward, leading to frequent falls.

The seizure event was characterized by widening of the eyeballs followed by flickering of right eyelids and tonic-clonic movement of all limbs. Around age 1 year the patient presented with status epilepticus, followed by seizure episode daily.

EEG and MRI data / Данные ЭЭГ и МРТ

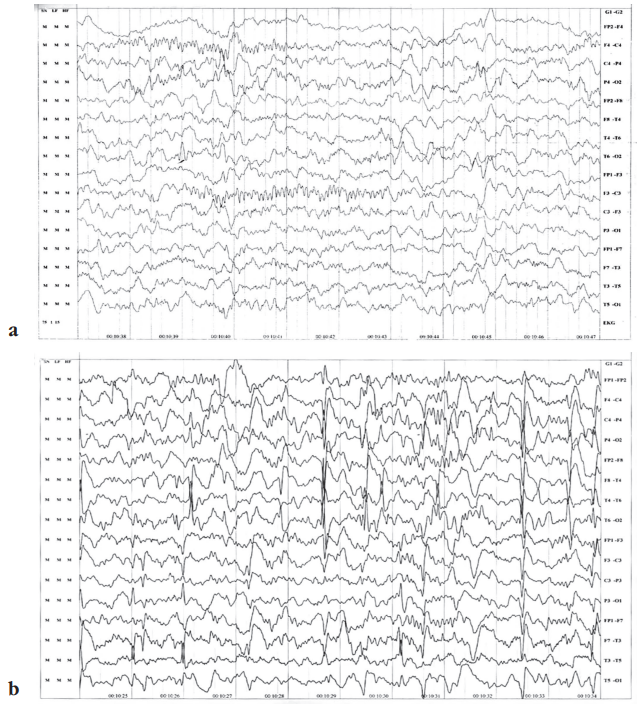

EEG during the initial presentation showed epileptiform activity from the left temporal region (Fig. 1a). Subsequently, EEG at 2.5 years showed inter-ictal bi-hemispheric epileptiform activity. EEG at 5 years showed inter-ictal spikes and wave discharges from bilateral fronto-temporal region with secondary generalization (Fig. 1b).

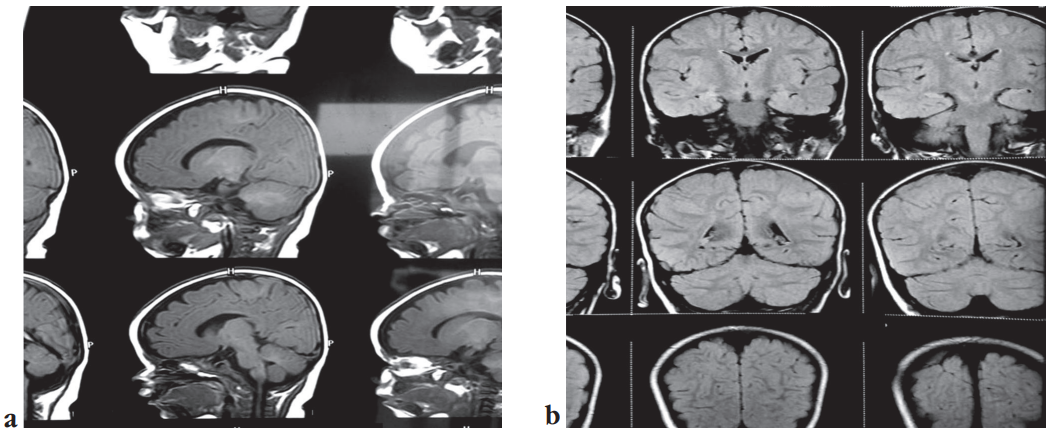

At age 3.5 months, MRI was normal with no focal abnormality seen (Fig. 2a). By 3 years, MRI showed mildly deformed corpus callosum with inadequate thickening of splenium (Fig. 2b).

Figure 1. Electroencephalography data: a – epileptiform activity from the left temporal region during the initial presentation at age 3 months; b – inter-ictal spikes and wave discharges from bilateral fronto-temporal region with secondary generalization at age 5 years

Рисунок 1. Данные электроэнцефалографии пациентки: а – эпилептиформная активность в левой височной области при первичном проявлении в возрасте 3 мес; b – межприступные спайки и волновые разряды в двусторонней лобно-височной области с вторичной генерализацией в возрасте 5 лет

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance images without contrast: a – sagittal section, normal with no focal abnormality seen at age 3.5 months; b – coronal section, mild deformed corpus callosum with inadequate thickening of splenium at age 3 years

Рисунок 2. Результаты магнитно-резонансного исследования без контраста: a – сагиттальный план, нормальный вид, без очаговых аномалий (возраст 3,5 мес); b – коронарный план, умеренная деформация мозолистого тела с недостаточной толщиной валика (возраст 3 года)

DNA analysis / Анализ ДНК

DNA analysis confirmed heterozygous missense mutation in exon 16 of DEPDC5 gene, without chromosomal abnormalities. Mother is heterozygous for the same mutation and father is normal.

The patient has grossly delayed milestones. The corrected age is approximately 1 year for Fine motor and Language, 1.5 years for Gross motor, 2.5 years for Cognition, Social, and Emotional skills. She has autism, impaired auditory/visual processing, and is hypersensitive to external stimuli. She has hypotonia (Right>Left), wide-based gait, and extrapyramidal movements.

Developmental growth / Возрастное развитие

On examination of the first episode of seizure at 3.5 months, the patient had no response to name and short attention span, no crawling. She had head control and turned prone.

10.5 months: the child showed response to name, short attention span, stereotypes, tried to reach to object.

1 year 7 months: the patient recognized parents, throwed and held objects, made single vowel sounds, began separation anxiety, established meaning of no.

2 year 3 months: the child stood with support, walked a few steps with support, had multiple stereotypes.

3 years: she had action tremors, no orientation respond to simple command, mixed ataxia, started speaking bisyllables words.

5 years: the patient had wide based gait and extrapyramidal movements which increased during evening, comprehended the command, meaningless bisyllables, biting repetitive activities.

6 years: she walked with support, was not toilet trained, had hypotonia Rt>Lt.

Chronological therapy / Терапия

Physiotherapy started at 6 months. Occupational therapy and sensory integration treatment started at 8 months.

After administering infant/toddler sensory profile (7–36 months) the patient had probably low functioning in auditory and visual processing areas. She was hypersensitive to tactile, auditory and proprioceptive stimulation and had bilateral integration problems.

Speech therapy started at 2 years. The patient still couldn't perform regular activities, played and talked normally.

Due to physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy and special education on a daily basis, the improvements were found.

Currently, the patient is on topiramate (100 mg twice daily), oxcarbazepine (5 ml twice daily), clobazam (5 mg twice daily).

DISCUSSION / ОБСУЖДЕНИЕ

DEPDC5 familial epilepsy syndrome comprises a collection of epilepsy conditions triggered by the stimulation of the mTOR pathway. This syndrome is linked to mutations in the newly identified DEPDC5 gene. This gene is a component of the GATOR1 complex, which plays a role in overseeing the signaling of the mTOR pathway [1]. The DEPDC5 gene plays a crucial role in shaping the dendrites and spines of neurons, and when this function is disrupted by mutations in DEPDC5, it can lead to increased excitatory transmission and the development of epilepsy; moreover, abnormal shaping of neurons is linked to neuropsychiatric disorders, explaining the observed psychiatric and autistic symptoms in patients with DEPDC5 mutations [3].

The precise occurrence and prevalence of DEPDC5 familial epilepsy syndromes remain insufficiently established. However, C. Martin et al.'s research into recurrent epilepsy linked with DEPDC5 mutations identified an incidence of 5% (4/79) among individuals with such mutations [4]. Mutations in the DEPDC5 gene could potentially explain up to 10% of cases of familial focal epilepsy [4]. Furthermore, L.M. Dibbens et al. indicated that among 82 families afflicted by the disorder, 12% exhibited the DEPDC5 mutation, underscoring its role as a potential cause of familial epilepsy syndrome [6]. Within a sample of 15 families affected by familial epilepsy syndrome, the DEPDC5 gene harbored five mutations: one missense mutation and four nonsense mutations. This same study revealed that there is evidence suggesting that 37% of patients with familial epilepsy syndrome carry a loss-of-function mutation in the DEPDC5 gene [8].

Table 1 discusses pediatric and adolescent familial epilepsy syndromes, which comprises a range of genetic disorders characterized by recurrent seizures typically emerging during childhood or adolescence. These syndromes, including Dravet syndrome, childhood absence epilepsy, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, benign familial neonatal epilepsy, and early myoclonic encephalopathy, result from mutations in various genes such as SCN1A, GABRG2, EFHC1, KCNQ2, KCNQ3, and STXBP1. The inheritance patterns vary, with some following autosomal dominant patterns (e.g., benign familial neonatal epilepsy, early myoclonic encephalopathy) and others being sporadic (e.g., Lennox–Gastaut syndrome). Understanding these genetic factors is essential for accurate diagnosis, management, and potential treatments of these epilepsy syndromes. Ongoing research continues to unveil new mutations and genes associated with these conditions.

Table 2 offers a concise summary of several research studies focused on different diseases, the associated genetic mutations, and the more recent targeted therapies employed for their treatment. These investigations provide insights into potential advancements in managing various medical conditions and enhancing patient outcomes. In our case study, the patient is currently undergoing a triple therapy regimen consisting of topiramate 100 mg twice daily, clobazam 5 mg twice daily, and oxcarbazepine 5 ml twice daily. Additionally, the patient is receiving a combination of physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy. Despite this comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach, the patient has not yet achieved complete recovery. This underscores the critical need for the development of innovative-targeted therapy approaches.

Table 3 encompasses a compilation of studies delving into DEPDC5-related epilepsy, a specific type of genetic focal epilepsy. Most of these studies revealed normal results in brain MRI scans, with the exception of a single study reporting a mix of normal and abnormal findings [22]. DEPDC5 mutations were identified across all the studies, and the individuals included in the research covered a wide range of age groups. Additional assessments, such as EEG and genetic testing, were conducted to confirm the presence of DEPDC5 mutations. The primary approach to managing this condition typically involved the administration of antiepileptic medications, though the response to treatment varied among individuals.

Table 1. The types of mutations and the inheritance pattern

Таблица 1. Типы мутаций и модель наследования

|

Study / Исследование |

Epilepsy syndrome / Синдром эпилепсии |

Mutation / Мутация |

Gene / Ген |

Inheritance pattern / Модель наследования |

|

A.C. Bender et al. [9] |

Dravet syndrome / Синдром Драве |

SCN1A |

Sodium channel, voltage-gated, type 1 alpha subunit / Натриевый канал, потенциал-зависимый, альфа-субъединица типа 1 |

Autosomal dominant / Аутосомно-доминантная |

|

S.E. Hunter et al. [10] |

Childhood absence epilepsy / Детская абсансная эпилепсия |

GABRG2 |

Gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit gamma-2 / Субъединица гамма-2 рецептора гамма-аминомасляной кислоты |

Autosomal dominant / Аутосомно-доминантная |

|

S. Ganesh et al. [11] |

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy / Ювенильная миоклоническая эпилепсия |

EFHC1 |

EF-hand domain-containing protein 1 / Белок 1, содержащий домен EF-hand |

Autosomal dominant / Аутосомно-доминантная |

|

J.O. Yang et al. [12] |

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome / Синдром Леннокса–Гасто |

Unknown (multiple possible) / Неизвестно (возможно несколько) |

Various genes, including SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN1B, GABRB3, GABRA1, among others / Различные гены, в т.ч. SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN1B, GABRB3, GABRA1 и др. |

Mostly sporadic, but some cases with possible genetic predisposition / В основном спорадическая, в ряде случаев с возможной генетической предрасположенностью |

|

M.K.C. Diallo et al. (actual case report) / M.K.C. Diallo et al. (представленный клинический случай) |

Familial epilepsy syndrome / Семейная эпилепсия |

DEPDC5 |

p. R389H |

Autosomal dominant / Аутосомно-доминантная |

|

F. Miceli et al. [13] |

Benign familial neonatal epilepsy / Доброкачественная семейная неонатальная эпилепсия |

KCNQ2, KCNQ3 |

Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q members 2 and 3 / Белки 2 и 3 подсемейства потенциал-зависимых калиевых каналов Q |

Autosomal dominant / Аутосомно-доминантная |

|

Y. Khaikin et al. [14], D. Abramov et al. [15] |

Early myoclonic encephalopathy / Ранняя миоклоническая энцефалопатия |

STXBP1 |

Syntaxin-binding protein 1 / Синтаксин-связывающий белок 1 |

Autosomal dominant / Аутосомно-доминантная |

Table 2. A concise summary of various research studies on different diseases, highlighting the associated genetic mutations and the recent targeted therapies used for treatment, along with their outcomes

Таблица 2. Краткая характеристика исследований различных заболеваний с указанием связанных с ними генетических мутаций, современных методов таргетной терапии и полученных результатов

|

Study / Исследование |

Study subject / Предмет исследования |

Mutation name / Название мутации |

Newer target therapies / Новые варианты таргетной терапии |

Outcomes / Исходы |

|

B. Patrick et al. [16] |

Epilepsy syndrome / Эпилептический синдром |

TCS1 mutation / Мутация TCS1 |

Rapamycin / Рапамицин |

Improved seizures / Улучшение контроля приступов |

|

K. Lindsay et al. [17] |

Familial epilepsy syndrome / Семейная эпилепсия |

DEPDC5 |

mTOR inhibitor / Ингибитор mTOR |

Improved seizures / Улучшение контроля приступов |

|

L.H. Zeng et al. [18] |

Tuberous sclerosis complex / Комплекс туберозного склероза |

TSC gene inactivation leads to hyperactivation of the mammalian target of rapamycin / Инактивация гена TSC приводит к гиперактивации мишени рапамицина в клетках млекопитающих |

mTOR |

Prevention of epilepsy in a mouse model / Предупреждение эпилепсии в мышиной модели |

|

R.H. Caraballo et al. [19] |

Dravet syndrome / Cиндром Драве |

SCNA1 |

Ketogenic diet vs. vagal nerve stimulation / Кетогенная диета в сравнении со стимуляцией блуждающего нерва |

Improvement in both patients with ketogenic diet and vagal nerve stimulation / Улучшение у пациентов и на фоне кетогенной диеты, и при стимуляции блуждающего нерва |

|

A. Winczewska-Wiktor et al. [20] |

Pediatricand adolescent patients with epilepsy / Пациенты детского и подросткового возраста с эпилепсией |

CACNA1S, CHD2, DEPDC5, KIF1A, PIGN, SCN1A, SCN8A, SLC2A1, SYNGAP1 pathogenic variants / Патогенные варианты CACNA1S, CHD2, DEPDC5, KIF1A, PIGN, SCN1A, SCN8A, SLC2A1, SYNGAP1 |

Ketogenic diet / Кетогенная диета |

Noteworthy effectiveness in patients with various types of seizures / Заметная эффективность у пациентов с различными типами приступов |

|

C. J. Yuskaitis et al. [21] |

Neuronal Depdc5 loss / Потеря нейрональной экспрессии Depdc5 |

DEPDC5 mutation / Мутация DEPDC5 |

mTORC1 inhibition / Подавление mTORC1 |

Rescue of deficits from neuronal Depdc5 loss in mice / Устранение дефицита потери нейрональной экспрессии Depdc5 у мышей |

Table 3 (начало). A compilation of studies delving into DEPDC5-related epilepsy, a specific type of genetic focal epilepsy

Таблица 3 (beginning). Исследования по изучению эпилепсии, связанной с мутацией в гене DEPDC5 (особого типа генетической фокальной эпилепсии)

|

Study / Исследование |

Type of study / Тип исследования |

Disease name / Название заболевания |

Demographic information / Демографические данные |

Presenting symptoms / Cимптомы |

Radiological findings / Рентгенологические данные |

Other tests / Прочие тесты |

Management / Лечение |

Outcomes / Исходы |

|

L.M. Dibbens et al. [6] |

Case series / Серия случаев |

DEPDC5 familial epilepsy / Семейная эпилепсия DEPDC5 |

Adults and children / Взрослые и дети |

Focal seizures / Фокальные приступы |

Normal brain MRI / Нормальная МРТ головного мозга |

Genetic testing shared homology with G protein signaling molecules and localization in human neurons / Генетическое тестирование показало гомологию с сигнальными молекулами G-белка и локализацию в нейронах человека |

AEDs / ПЭП |

Variable response / Вариабельный ответ |

|

X. Zhang et al. [7] |

Case report / Клинический случай |

DEPDC5-related epilepsy / Эпилепсия, связанная с мутацией в гене DEPDC5 |

Chinese family with age ranging from 3 months to 45 years / Члены китайской семьи в возрасте от 3 мес до 45 лет |

Shouting, paroxysmal unconsciousness and limb stiffness preceded or not whether with an aura of fear, or deja vu, tonic-clonic seizure or simply tonic seizure / Крик, пароксизмальная потеря сознания и скованность конечностей, которым предшествовала или нет аура страха или дежавю, тонико-клонические или просто тонические приступы |

Normal brain MRI (no mesial temporal sclerosis, no cortical dysplasia, no polymicrogyria or other structural abnormalities / Нормальная МРТ головного мозга (без мезиального височного склероза, корковой дисплазии, полимикрогирии и прочих структурных аномалий) |

Genetic testing(missense mutations (c.1729>A and c.3260G>A), one splicing mutation (c.280-1G>A), and one frameshift mutation (c.515_516delinsT) / Генетическое тестирование (миссенс-мутации (c.1729>A и c.3260G>A), одна мутация сплайсинга (c.280-1G>A) и одна мутация сдвига рамки считывания (c.515_516delinsT) |

AEDs (levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenobarbital) / ПЭП (леветирацетам, окскарбазепин, вальпроат, карбамазепин, ламотриджин, фенобарбитал) |

Partial seizure control, refractory to most AEDs / Частичный контроль приступов, резистентный к большинству ПЭП |

|

S. Baldassari et al. [22] |

Case series / Серия случаев |

Genetic focal epilepsies / Генетические фокальные эпилепсии |

Children with average age of 4.4 years / Дети со средним возрастом 4,4 года |

Focal seizures,s in 50% of patients, infantile spasms in 10% of probands, SUDEP in 10% of families / Фокальные приступы у 50% пациентов, инфантильные спазмы у 10% пробандов, SUDEP в 10% семей |

Normal or abnormal (focal cortical dysplasia in 20% of cases) / Нормальная или атипичная (очаговая корковая дисплазия в 20% случаев) |

EEG (hypermotor or frontal lobe seizure), genetic testing (68% are loss-of-function pathogenic, 14% are likely pathogenic, 15% are variants of uncertain significance and 3% are likely benign / ЭЭГ (гипермоторный или лобный приступ), генетическое тестирование (68% – патогенные, вызывающие потерю функции, 14% – вероятно патогенные, 15% – варианты неопределенной значимости, 3% – вероятно доброкачественные) |

AEDs / ПЭП |

Variable response / Вариабельный ответ |

Table 3 (окончание). A compilation of studies delving into DEPDC5-related epilepsy, a specific type of genetic focal epilepsy

Таблица 3 (end). Исследования по изучению эпилепсии, связанной с мутацией в гене DEPDC5 (особого типа генетической фокальной эпилепсии)

|

Study / Исследование |

Type of study / Тип исследования |

Disease name / Название заболевания |

Demographic information / Демографические данные |

Presenting symptoms / Cимптомы |

Radiological findings / Рентгенологические данные |

Other tests / Прочие тесты |

Management / Лечение |

Outcomes / Исходы |

|

M.K.C. Diallo et al. (actual case report) / M.K.C. Diallo et al. (представленный клинический случай) |

Case report / Клинический случай |

DEPDC5 mutations in familial epilepsy syndrome / Мутации в гене DEPDC5 при семейной эпилепсии |

6 year old / 6 лет |

Generalized seizures / Генерализованные приступы |

Abnormal brain MRI characterized by mildly deformed corpus callosum with inadequate thickening of the splenium by the age of 3 years / Атипичная МРТ головного мозга с умеренной деформацией мозолистого тела и недостаточной толщиной его валика к возрасту 3 лет |

Genetic testing (heterozygous missense mutation in exon 16 of the DEPDC5 gene, without any chromosomal abnormalities / Генетическое тестирование (гетерозиготная миссенс-мутация в экзоне 16 гена DEPDC5 без каких-либо хромосомных аномалий) |

AEDs (topiramate, oxcarbazepine, clobazam and supportive therapy / ПЭП (топирамат, окскарбазепин, клобазам и поддерживающая терапия) |

Some improvement is noted / Отмечено некоторое улучшение |

Note. AEDs – anti-epileptic drugs; MRI – magnetic resonance imaging; EEG – electroencephalography; SUDEP – sudden unexplained death in epilepsy.

Примечание. ПЭП – противоэпилептические препараты; МРТ – магнитно-резонансная томография; ЭЭГ – электроэнцефалография; SUDEP (англ. sudden unexplained death in epilepsy) – внезапная необъяснимая смерть при эпилепсии.

In our own case report, a DNA analysis confirmed the presence of a heterozygous missense mutation in exon 16 of the DEPDC5 gene, with no observed chromosomal abnormalities. Our case report also highlighted an abnormal MRI result, characterized by a mildly deformed corpus callosum with insufficient thickening of the splenium by the age of 3 years (see Fig. 2b). However, the MRI conducted at approximately 3.5 months of age yielded inconclusive results (see Fig. 2a).

The strength of this case lies in the confirmation of genetic testing aligning with the abnormal MRI findings, specifically the mildly deformed corpus callosum with inadequate thickening of the splenium (see Fig. 2a). Additionally, the EEG assessments at various time points (3 months, around 2.5 years, and 5 years) further support the diagnosis, with observations of epileptiform activity from the left temporal region at 3 months (see Fig. 1a), inter-ictal bi-hemispheric epileptiform activity around 2.5 years, and interictal spikes and wave discharges from the bilateral fronto-temporal region with secondary generalization at 5 years (see Fig. 1b).

It is important to note that while these findings validate the specific case under consideration, they cannot be generalized as representative of all cases due to the unique nature of each individual's condition. Besides, we do not have a full familial and/or hereditary picture of the patient except for the fact that the mother is heterozygous for the mutation.

Future directions / Направления дальнейших исследований

Valuable insights into the clinical features, diagnostic tools, and management of DEPDC5 gene mutation familial epilepsy syndrome are needed to shed light on this rare and challenging diagnosis. The variability in brain MRI results, ranging from positive to negative findings, further adds to the complexity of the syndrome. Despite advancements in genetic testing and personalized medicine, some patients still do not respond to treatment, highlighting the need for further research and therapeutic advancements. The rarity of the disease and the challenges it presents serve as compelling reasons to document this case report on DEPDC5 gene mutation familial epilepsy syndrome, aiming to enhance understanding and improve patient care in the future.

CONCLUSION / ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

DEPDC5 familial epilepsy syndrome is a group of epilepsy disorders caused by mutations in the DEPDC5 gene, which is part of the GATOR1 complex involved in regulating the mTOR pathway. These mutations lead to hyperactivation of the mTOR pathway, disrupting the shaping of neurons and resulting in increased excitatory transmission and the development of epilepsy. The incidence and prevalence of DEPDC5 familial epilepsy syndromes are not well established, but studies suggest it may account for up to 10% of familial focal epilepsy cases. Genetic testing, EEG, and brain MRI are important in diagnosing the disorder, although normal MRI results are common.

References

1. Samanta D. DEPDC5-related epilepsy: a comprehensive review. Epilepsy Behav. 2022: 130: 108678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2022.108678.

2. Ververi A., Zagaglia S., Menzies L., et al. Germline homozygous missense DEPDC5 variants cause severe refractory early-onset epilepsy, macrocephaly and bilateral polymicrogyria. Hum Mol Genet. 2023; 32 (4): 580–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddac225.

3. Ribierre T., Deleuze C., Bacq A., et al. Second-hit mosaic mutation in mTORC1 repressor DEPDC5 causes focal cortical dysplasia-associated epilepsy. J Clin Invest. 2018; 128 (6): 2452–8. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI99384.

4. Martin C., Meloche C., Rioux M.F., et al. A recurrent mutation in DEPDC5 predisposes to focal epilepsies in the French-Canadian population. Clin Genet. 2014; 86 (6): 570–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12311.

5. Mabika M., Agbogba K., Côté S., et al. Neurophysiological assessment of cortical activity in DEPDC5- and NPRL3-related epileptic mTORopathies. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023; 18 (1): 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-022-02600-6.

6. Dibbens L.M., de Vries B., Donatello S., et al. Mutations in DEPDC5 cause familial focal epilepsy with variable foci. Nat Genet. 2013; 45 (5): 546–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2599.

7. Zhang X., Huang Z., Liu J., et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of DEPDC5-related familial focal epilepsy: case series and literature review. Front Neurol. 2021; 12: 641019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.641019.

8. Ishida S., Picard F., Rudolf G., et al. Mutations of DEPDC5 cause autosomal dominant focal epilepsies. Nat Genet. 2013; 45 (5): 552–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2601.

9. Bender A.C., Morse R.P., Scott R.C., et al. SCN1A mutations in Dravet syndrome: impact of interneuron dysfunction on neural networks and cognitive outcome. Epilepsy Behav. 2012; 23 (3): 177–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.11.022.

10. Hunter S.E., Jalazo E., Felton T.R., et al. Epilepsy genetics: advancements in the field and impact on clinical practice. In: Czuczwar S.J. (Ed.). Epilepsy. Chapter 3. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications; 2022. Available at: https://exonpublications.com/index.php/exon/article/view/epilepsy-genetics/902 (accessed 20.05.2024).

11. Ganesh S. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: EFHC1 at the cross-roads? Ann Neurosci. 2010; 17 (2): 57–9. https://doi.org/10.5214/ans.0972-7531.1017202.

12. Yang J.O., Choi M.H., Yoon J.Y., et al. Characteristics of genetic variations associated with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome in Korean families. Front Genet. 2021; 11: 590924. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.590924.

13. Miceli F., Soldovieri M.V., Weckhuysen S., et al. KCNQ3-related disorders. 2014 May 22. In: Adam M.P., Mirzaa G.M., Pagon R.A., et al. (Eds.) GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington; 1993–2023.

14. Khaikin Y., Mercimek-Andrews S. STXBP1 encephalopathy with epilepsy. 2016 Dec 1. In: Adam M.P., Mirzaa G.M., Pagon R.A., et al. (Eds.) GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington; 1993–2023.

15. Abramov D., Guiberson N.G.L., Burré J. STXBP1 encephalopathies: clinical spectrum, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies. J Neurochem. 2021; 157 (2): 165–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.15120.

16. Moloney P.B., Cavalleri G.L., Delanty N. Epilepsy in the mTORopathies: opportunities for precision medicine. Brain Commun. 2021; 3 (4): fcab222. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcab222.

17. Klofas L.K., Short B.P., Zhou C., Carson R.P. Prevention of premature death and seizures in a Depdc5 mouse epilepsy model through inhibition of mTORC1. Hum Mol Genet. 2020; 29 (8): 1365–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddaa068.

18. Zeng L.H., Xu L., Gutmann D.H., Wong M. Rapamycin prevents epilepsy in a mouse model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Ann Neurol. 2008; 63 (4): 444–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.21331.

19. Caraballo R.H. Nonpharmacologic treatments of Dravet syndrome: focus on the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2011; 52 (Suppl. 2): 79–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03009.x.

20. Winczewska-Wiktor A., Hirschfeld A.S., Badura-Stronka M., et al. Analysis of factors that may affect the effectiveness of ketogenic diet treatment in pediatric and adolescent patients. J Clin Med. 2022; 11 (3): 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11030606.

21. Yuskaitis C.J., Rossitto L.A., Gurnani S., et al. Chronic mTORC1 inhibition rescues behavioral and biochemical deficits resulting from neuronal Depdc5 loss in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2019; 28 (17): 2952–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddz123.

22. Baldassari S., Picard F., Verbeek N.E., et al. The landscape of epilepsy-related GATOR1 variants. Genet Med. 2019; 21 (2): 398–408. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0060-2.

About the Authors

M. K.C. DialloUnited States

Mamadou Kindy Cherif Diallo.

611 W Park Str., Urbana, IL 61801

S. Mukesh

Pakistan

Sindu Mukesh.

C7P9+4W6, Jamshoro, Sindh

L. Kapil

Netherlands Antilles

Leslie Kapil.

25 Pater Euwensweg, Willemstad, Curacao

R. Singla

United States

Ramit Singla.

2435 Forest Dr., Columbia, SC 29204

Scopus Author ID 57216049043

D. Tar

United States

Deen Tar.

1310 Club D., Vallejo, CA 94592

S. N. Tammineedi

India

Sai Niharika Tammineedi.

56W7+RC5, Akkenepally vari lingotam, Narketpalle, Telangana 508254

E. Singer

United States

Emad Singer.

1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030

H. Chhayani

India

Hiren Chhayani.

Old TB hospital Campus, Gotri Rd, Gotri, Vadodara, Gujarat 390021

K. Arumaithurai

United States

Kogul Arumaithurai.

404 W Fountain St, Albert Lea, MN 56007

U. K. Patel

United States

Urvish K. Patel.

1 Gustave L. Levy Pl, New York, NY 10029

Scopus Author ID 57205649495

R. Arora

United States

Rohan Arora.

500 Hofstra Blvd, Hempstead, NY 11549

Review

For citations:

Diallo M.K., Mukesh S., Kapil L., Singla R., Tar D., Tammineedi S.N., Singer E., Chhayani H., Arumaithurai K., Patel U.K., Arora R. DEPDC5 mutations in familial epilepsy syndrome: genetic insights and therapeutic approaches. Epilepsy and paroxysmal conditions. 2024;16(4):338-348. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2024.193

JATS XML

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.