Scroll to:

Experiences of people living with epilepsy regarding treatment and interventions in selected rural communities of Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces, South Africa

https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2025.216

Abstract

Background. Cultural beliefs, attitudes, and traditions play a crucial role in shaping epilepsy treatment preferences. Rather than obtaining medical interventions, most clients may prefer spiritual healing or traditional healers. This may cause delays in early diagnosis and appropriate epilepsy medical care, thereby increasing the risk of complications.

Objective: to investigate experiences of people living with epilepsy (PLWE) regarding care or interventions they receive from professional nurses, faith-based healers, and traditional healers in rural communities of Limpopo and Mpumalanga, South Africa. Material and methods. A qualitative approach using exploratory, descriptive and contextual designs was employed to attain the objectives of the study. In-depth individual interviews were conducted to collect data, and analysis was performed using Tesch’s eight steps of data analysis. The sample comprised 25 PLWE in selected rural communities.

Results. Three themes emerged from the data: experiences with care by traditional healers, experiences with care by faithbased healers, and experiences of care by professional nurses at local clinics. The findings revealed that many PLWE preferred care provided by traditional healers and faith-based healers over modern medical treatment from the local clinics, even though they were not always effective. Modern treatment was usually considered at a later stage, causing delays in diagnosis and theraphy. Treatment preferences are significantly influenced by cultural beliefs, values, and practices. Individuals with epilepsy who think their condition is spiritual in nature opt to receive treatment from traditional or faith-based healers. On the other hand, antiepileptic medications from nearby clinics are preferred by those who think there is a medical cause.

Conclusion. The results of the study demonstrated the necessity of creating culturally congruent approaches that honour the values and customs of PLWE, fostering a feeling of community and supporting the delivery of comprehensive care.

Keywords

For citations:

Nemathaga M., Maputle M.S., Makhado L., Mashau N.S. Experiences of people living with epilepsy regarding treatment and interventions in selected rural communities of Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces, South Africa. Epilepsy and paroxysmal conditions. 2025;17(2):161-169. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2025.216

INTRODUCTION / ВВЕДЕНИЕ

Individuals who live in rural communities with varied cultural origins and have epilepsy often face unique challenges in their daily lives [1]. The treatment and interventions provided by professional nurses, traditional healers, and faith-based healers have a significant impact on their well-being [2]. Some rural populations prefer to use modern medical treatments like antiepileptic medicines (AEDs) to treat epilepsy, while others mainly rely on traditional medicine or spiritual rituals [3][4). Experiences and decisions are greatly influenced by the cultural practices and beliefs of individuals. Preferences for treatment are often influenced by myths surrounding epilepsy.

The neurological disorder known as epilepsy is characterized by periodic seizures [5][6]. Roughly 50 million people are impacted globally, with a higher frequency in Africa [7][8]. The World Health Organization (WHO) predicts that 80 percent of Africans who have epilepsy live in low- and middle-income nations [9][10]. Regretfully, most people living with epilepsy (PLWE) do not obtain the proper medical attention and therapy [11].

Professional nurses are usually the first option for individuals seeking medical assistance to control seizures [12][13]. In addition to making sure patients receive the appropriate treatment and follow-up care, they offer evidence-based treatment. However, in rural communities with limited access to healthcare services and diverse cultural backgrounds, professional nurses may not always be readily available or culturally accepted [14][15].

Traditional healers also play an important role in the lives of people living with epilepsy (PLWE) in rural communities, using herbal remedies, rituals, and spiritual practices to treat epilepsy [16][17]. The majority of PLWE from diverse cultural backgrounds rely on traditional healers, often stemming from their cultural beliefs, values, and practices [18]. Traditional healing modalities provide solace and a sense of community for those looking for alternative solutions. These customs are significant to the culture and provide solace, although they may not always be effective in treating epilepsy. PLWE can also receive assistance from faith-based healers. According to A.R. Hatala and Roger K. (2021) their healing practices consist of many rituals and prayers that stem from their spiritual beliefs [19]. Relying only on faith-based interventions may result in delays or obstacles to proper medical care, even though faith can give patients solace and hope. Many studies in Africa have explored the experiences of PLWE regarding modern evidenced-based treatment. However, experiences regarding other alternative interventions such as spiritual or traditional remedies have not been widely examined.

Objective: to investigate PLWE's experiences regarding care or interventions they receive from professional nurses, faith-based healers, and traditional healers.

MATERIAL AND METHODS / МАТЕРИАЛ И МЕТОДЫ

Study setting / Место исследования

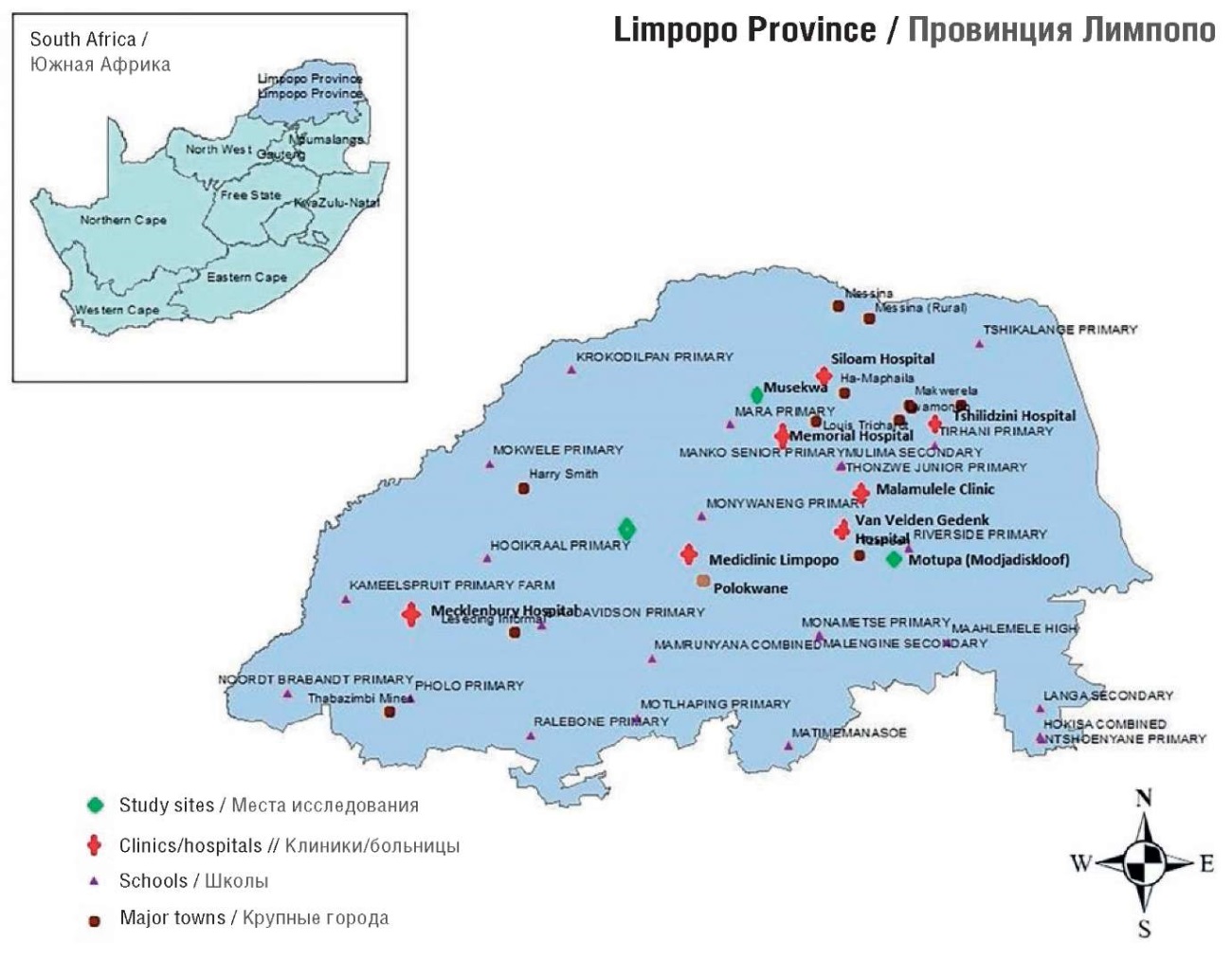

This study was conducted in selected rural communities in Limpopo and Mpumalanga. Provinces. The selected rural communities in Limpopo were Malavuwe, Mtititi, and Bochum, while the selected rural communities in Mpumalanga were Clara, Acornhoek, and Jerusalem. These communities were selected based on the prevalence of epilepsy cases and diversity of cultures. Figures 1, 2 represents the geographic locations of the study setting.

Figure 1. Limpopo Province map (South Africa)

Рисунок 1. Карта провинции Лимпопо (Южная Африка)

Figure 2. Mpumalanga Province map (South Africa)

Рисунок 2. Карта провинции Мпумаланга (Южная Африка)

Design / Дизайн

To accomplish its goals, this study undertook a qualitative approach utilizing exploratory, descriptive, and contextual methods [20][21]. To get comprehensive data, the researcher had direct interactions with the individuals.

Population and sampling / Популяция и выборка

Population included PLWE in selected rural communities in Limpopo and Mpumalanga. Purposive sampling was used to sample the villages (see Fig. 1) based on their cultural diversity. Using the snowball sampling method [20], the study sampled participants by having one person living with epilepsy recognized by community members who subsequently referred other PLWE. The researcher focused only on individuals living with epilepsy within the selected rural communities of Limpopo and Mpumalanga.

The study sample comprised 25 participants, the majority of whom were females (n=18), while only a few were male (n=7). The age of participants ranged between 25 and 55 years. Most of the participants (n=14) were from villages in Mpumalanga and (n=11) from Limpopo province. While most participants had dropped out due to uncontrollably occurring seizures and being stigmatized at school, a small number had succeeded in obtaining postsecondary degrees. The most common language was TshiVenda, which was followed by XiTsonga and then SePedi. Table 1 depicts the demographic profile of this study.

Table 1. Demographic profile of participants (n=25)

Таблица 1. Демографический профиль участников исследования (n=25)

|

Parameter / Параметр |

Number of participants, n (%) / Число участников, n (%) |

|

Age, years / Возраст, лет |

|

|

20–30 |

1 (4) |

|

31–40 |

8 (32) |

|

41–50 |

8 (32) |

|

51–60 |

8 (32) |

|

Gender / Пол |

|

|

male / мужской |

18 (72) |

|

female / женский |

7 (28) |

|

Marital status / Семейное положение |

|

|

married // женат/замужем |

10 (40) |

|

unmarried // не женат / не замужем |

15 (60) |

|

Ethnicity / Этническая принадлежность |

|

|

TshiVenda / тшивенда |

11 (44) |

|

XiTsonga / тсонга |

8 (32) |

|

SePedi / сепеди |

6 (24) |

|

Highest level of education / Уровень образования |

|

|

primary school / начальное |

8 (32) |

|

high school / среднее |

10 (40) |

|

post matric / высшее |

7 (28) |

|

Provider consulted for epilepsy / Лицо, консультировавшее по эпилепсии |

|

|

traditional healer / народный целитель |

12 48() |

|

medical practitioner /практикующий врач |

5 (20) |

|

faith-based healer / религиозный целитель |

3 (12) |

|

traditional & medical practitioner / народный целитель и практикующий врач |

3 (12) |

|

faith based healer & medical practitioner / религиозный целитель и практикующий врач |

2 (8) |

Data collection / Сбор данных

Pre-test of the interview question

The researcher pre-tested the questions with a group of PLWE rural community members at nearby clinics before beginning the actual data collection process. Interviews were conducted with the chosen individuals to find out how well they understood the questions' wording. According to H. Brink et al. [22], the pre-test lasted between thirty and fifty minutes. Participants who were interviewed for the pre-test were not included in this study.

Actual data collection

Individual, in-depth interviews were conducted at the PLWEs' homes to collect data. Thirty (30) to 45 minutes was the length of each interview. Local languages (Sepedi, XiTsonga, and TshiVenda) were used for the interviews. With permission from the participants, voice recordings of the interviews were made. This fundamental question served as the basis for the interviews: “In your views to manage your epilepsy, could you kindly tell me about your experiences regarding the treatment and interventions received?”

The probing focus was on the treatment provided by the traditional healers, faith-based healers and professional nurses. Based on the participants’ initial responses, probing questions were asked to elicit more detailed information and gain deeper insights. Techniques including listening, clarifying, reflecting, focusing, and paraphrasing were employed to obtain additional information from the participants. Subtle vocal signals such as nodding the head, saying “mm”, “Yes”, and “continue” encouraged participants to share information and enhanced the flow of conversation.

Data analysis / Анализ данных

The data was analysed according Tesch’s open coding analysis guide which comprises eight steps to be followed when analysing qualitative data. The researcher listened to the voice recordings repeatedly and transcribed them verbatim. Following that, each transcript was reviewed, one at a time, to ensure a clear understanding of the participants’ responses. Similar categories were noted down and clustered into categories. As sub-themes surfaced, they were organised into columns. Following that, related topics were grouped into columns. Different coloured pens were used to simplify the task. The researcher then abbreviated the topics as codes and annotated them with the relevant themes. The researcher used tables to present the results of the analysis. These tables were arranged using the themes, categories, and subcategories identified by the researcher.

Measures to ensure trustworthiness / Меры по обеспечению достоверности

To ensure trustworthiness, the criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability were adopted. Persistent observation and member checking were done to ensure credibility. Transferability was addressed by providing a thorough explanation of the study approach and results, as well as detailed background information to ensure transferability [20][21]. The methods used in this study were comprehensively documented to allow for replication by future researchers, thereby addressing dependability [23].

RESULTS / РЕЗУЛЬТАТЫ

According to the study's findings, most PLWE preferred spiritual healing and/or traditional interventions over contemporary healthcare. Some stated that they would rather have a mix of traditional and medical care, or spiritual and medical care, while the majority solely desired modern medical treatments. The experiences of receiving care from faith-based healers, from professional nurses at clinics, and from traditional healers emerged as three themes from the raw data. Table 2 summarises the themes and sub-themes that emerged.

Table 2. Study themes and sub-themes (experiences related to health-seeking behaviour when living with epilepsy)

Таблица 2. Темы и подтемы исследования (опыт здоровьесберегающего поведения при эпилепсии)

|

Theme / Тема |

Sub-theme / Подтема |

||

|

1 |

Seeking epilepsy health care from traditional healers / Обращение за медицинской помощью при эпилепсии к народным целителям |

1.1 |

Positive encounters with traditional healers' treatment / Позитивные впечатления от лечения у народных целителей |

|

1.2 |

Negative experiences with traditional healers' treatment / Негативные впечатления от лечения у народных целителей |

||

|

2 |

Seeking epilepsy health care from faith-based healers / Обращение за медицинской помощью при эпилепсии к религиозным целителям |

2.1 |

Positive encounters with faith-based healers' treatment / Позитивные впечатления от лечения у религиозных целителей |

|

2.2 |

Negative experiences with faith-based healers' treatment / Негативные впечатления от лечения у религиозных целителей |

||

|

3 |

Seeking epilepsy health care from health professional professionals / Обращение за медицинской помощью при эпилепсии к специалистам здравоохранения |

3.1 |

Positive encounters with medical care and treatment / Позитивные впечатления от медицинской помощи и лечения |

|

3.3 |

Challenges encountered when receiving medical care and interventions / Проблемы, возникшие при получении медицинской помощи и вмешательств при эпилепсии |

||

Theme 1. Seeking epilepsy health care from traditional healers / Тема 1. Обращение за медицинской помощью при эпилепсии к народным целителям

The study’s findings study revealed that traditional healing interventions are effective in reducing the frequency of seizures, sometimes stopping them altogetheR. Nevertheless, some PLWE reported that they did not find these interventions to be effective. Two sub-themes emerged from the theme: Positive encounters with traditional healers' care and negative experiences with traditional healers' treatment as discussed below.

Sub-theme 1.1. Positive encounters with traditional healers' treatment

According to the study's findings, a small number of PLWE had fewer seizures and responded effectively to the traditional healer’s therapies. It's interesting that several people said that the seizures totally stopped. The subsequent quotations corroborated the findings: One woman, aged 44, stated:

“When I initially experienced a seizure, a traditional healer treated me. For several days, I was under the care of the healer, who used steaming and herbal treatments to treat me. part of the herb mixture was burned and used for steaming, and I drank part of it. He was a big help to me because I haven't had any seizures since.”

"Traditional healers are very good in treating epilepsy, stated a 53-year-old male who also had a pleasant experience. I had frequent seizures all my life, which made things difficult because I couldn't accomplish most things. The traditional healer gave me some herbs, and these helped to lessen the seizures. I am currently leading a regular life without anyone closely observing me.”

A 57-year-old woman gave the following explanation:

“I sought advice from a traditional healer because I was experiencing frequent seizures, and I was hoping they would lessen or stop." The fact that the seizures don't happen right away indicates how powerful the traditional herbs I used were. I even forget that I have epilepsy sometimes.”

Sub-theme 1.2. Negative experiences with traditional healers' treatment

Some people with uncontrolled epilepsy reported that conventional healing methods did not work. As such, they turned to known to be successful medical therapies.

A 46-year-old female said:

“I went for follow-up care and took herbal treatments for a while, but the treatment did not work because the seizures persisted. Even though I had a ritual ceremony, nothing changed. I subsequently made the decision to seek medical advice at a nearby clinic. My seizures were under control just then. Every month, I receive treatment.”

A 49-year-old woman affirmed this, saying:

“I was advised by a relative to seek treatment from a popular traditional healer who was well-known for treating various diseases." He assured me that I would get better quickly and provided me some traditional herbs to drink three times a day. I wasn't feeling good at all, and my seizures were becoming more frequent after starting the treatment. For me, the therapy was ineffective.”

Theme 2. Seeking epilepsy health care from faith-based healers / Тема 2. Обращение за медицинской помощью при эпилепсии к религиозным целителям

The findings of the study showed that anointing oil, prayer, fasting, and prophetic deliverance were examples of faith-based interventions. While some PLWE encountered difficulties, others claimed that the treatments were beneficial. Two sub-themes emerged from this study: Positive encounters with faith-based healers and negative experiences with faith-based healers' treatment.

Sub-theme 2.1. Positive encounters with faith-based healers' treatment

The research results show that faith-based healing methods were effective in reducing seizures, which eventually stopped altogetheR. The data are illustrated by the quotes that follow:

A 51-year-old female explained:

“At Vhazalwane Church, where I attend, the pastor heals and provides prophetic deliverance to everyone who is ill. I was one of them, too, and I thought that since epilepsy was a spiritual condition, God would cure me of it. My seizures were much reduced when I used anointing oil, which was also quite beneficial.”

The other participant said:

“I believe that my illness was caused by witchcraft, so I sought [sic] deliverance from a prophet," stated a 38-year-old woman. After he prayed for me for some time, I was delivered since the seizures were no longer as common as they had been. I think I will be free as long as I continue to pray on a regular basis with the help of my prophet.”

Sub-theme 2.2. Negative experiences with faith-based healers' treatment

According to some research findings, successful treatment for epilepsy does not always involve faith-based healing approaches. Seizures were not controlled, as according to some PLWE. These results are corroborated by the following quotes.

A 58-year-old said:

“I fasted and prayed, and my pastor prayed for me. There was a brief decrease in the number of seizures. After that, they kept coming back, so I visited the clinic and received therapy. There is a noticeable change, which indicates that the clinic's treatment is quite beneficial. The number of seizures is decreased.”

A 51-year-old woman explained, saying:

"I heard about a prophet who was healing all diseases and doing miracles. After that, I went to the chapel where I was instructed to buy holy water and anointing oil. Before I began having strange nightmares, I used such products for a while, but they never seemed to help. After I stopped using, I visited the clinic.”

Theme 3. Seeking epilepsy health care from health professionals / Тема 3. Обращение за медицинской помощью при эпилепсии к специалистам здравоохранения

According to the study, most PLWE thought that medical interventions were very beneficial because they reduced their seizures, which enhanced their quality of life. There have been reports of several difficulties, including a shortage of AEDs. Two subthemes emerged from this theme namely; positive encounters with medical care and treatment, challenges encountered when receiving epilepsy medical care and interventions.

Sub-theme 3.1. Positive encounters with medical care and treatment

The majority of PLWE confirmed that medical treatment controlled their seizures and significantly improved their quality of life, as elaborated by the following quotes:

“I’ve been using medical treatment for such a long time now and it’s very effective,” said a 33-year-old man. I can now perform most tasks just like anyone else, which has greatly improved my quality of life. I make sure to take my medication as directed and in the right dosage.”

A 30-year-old woman said:

“The clinic treatment I use is effective. Seizures are something I only occasionally get, and they pass quickly. I have no trouble working from home and completing my tasks. Since I started using the therapy in high school, I have not had any issues.”

Sub-theme 3.2. Challenges encountered when receiving medical care and interventions

Despite reports that medical intervention might control seizures, obstacles like the lack of AEDs and travel time to nearby clinics were mentioned. The following quotations provided the following evidence.

A 34-year-old woman said.

“I use the white round tablets, and they really help," I simply can't stop taking the medication; therefore, I have to buy them from the pharmacy when they're not always available at the clinic. Just that I don't have a job, so it's still difficult. My family is put through needless hardship because the government must help.”

A 31-year-old male elaborated:

“My local clinic provides highly effective treatment. The problem is that when I go back for a review, they're not always available, which is not ideal. My life becomes more difficult, and my seizures worsen if I don't take the medication. I live quite a distance away from the clinic. Only if a mobile clinic could be located nearby.”

DISCUSSION / ОБСУЖДЕНИЕ

The findings of this study revealed that the majority of PLWE consulted traditional healers and faith-based healers as a first option. These findings are similar to those of M. Nemathaga et al. [26] and Q. Chabangu et al. [18] who indicated that numerous people living with epilepsy in rural communities prefer care provided by traditional and faith-based healers as their first option. The treatment that medical professionals provide is not given priority, which causes needless delays in epilepsy diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, P. Anand et al. [27] found that even in cases where they have access to contemporary medical care, the majority of PLWE chose treatment from traditional healers.

The majority of PLWE had bad experiences while seeking care, whereas very few had good one. For those for whom the measures proved ineffective in controlling their seizures, medical treatment was a last resort. According to research by J.S. Corneille and D. Luke [28], a lot of people have reported having positive experiences with traditional healers, reporting increases in their overall sense of wellness, emotional stability, and a decrease in seizures. Moreover, a great deal of people also talk of feeling reconnected to their culture and society, as well as revitalized hope about the future.

The cultural beliefs, attitudes, and practices of PLWE have a significant impact on the preference for treatments or therapies. These results are in line with other research showing that some individuals receive solace and cultural familiarity from traditional healers that they are unable to get in contemporary treatment. M.G. Mokgobi [29] corroborated the results, demonstrating that African traditional healers (who are regarded as "medical knowledge storehouses") are incredibly resourceful and occupy important roles as traditional culture, cosmology, and spirituality educators. In addition, they have a significant impact on a variety of facets of the lives of those they assist. Not only do they preserve traditional wisdom, but they also serve as competent social workers, counsellors, and psychotherapists. These healers treat epilepsy through herbal treatments, spiritual practices, and rituals. To treat epileptic symptoms, traditional healers frequently use a variety of techniques, such as herbal remedies, meditation, and dietary adjustments. Many patients comment on how these professionals help them feel understood and supported since they incorporate their cultural beliefs into the therapeutic process [18][26][30]. Additionally, many patients with epilepsy seek the assistance of these traditional and faith-based healers because they believe in traditional healing practices and want holistic care. As noted by N. Mohamed and H.E. Babikir [31], Africans, who were groomed with specific cultural beliefs, prefer using traditional and spiritual remedies to control seizures. Moreover, it was further documented that a significant number of people strongly hold the belief that epilepsy has a spiritual origin, with approximately 70.5% of people seeking treatment from traditional healers and faith-based healers before seeking medical attention [31].

The study's results did, however, also show that some PLWE had unfavourable experiences with conventional healing methods since their seizures remained uncontrolled for a long time, delaying the detection and treatment of epilepsy. D.C. Koltai et al. [14] also made notice of this, citing multiple accounts of unfavourable experiences with the application of traditional medicine. Numerous individuals have found interventions that are based on traditional healing practices or faith-based did not provide any benefits in controlling seizures. This led to frustration and disappointment, as well as wasted time and resources spent on ineffective treatments. Moreover, according to a study conducted by M. Nemathaga et al. [26], no scientific evidence exists regarding anti-seizure components in traditional medicine, which explains why, in some instances seizures are not controlled.

The results also imply that people with epilepsy who sought consultation at local clinics stated that AEDs were successful in managing their condition since they reduced seizure frequency, which considerably enhanced their quality of life. Fascinatingly, WHO research from 2012 found that the most widely given AEDs in Africa, according to 65–85% of patients, are phenytoin and phenobarbital, which are also the least expensive. Though other extremely effective epilepsy drugs like valproic acid and carbamazepine are also available, their cost is much higher [32]. Several challenges were raised during this study, including the unavailability of treatment at times and long walking distance to local clinics. These challenges may hinder the provision of quality health care and treatment adherence, potentially leading to complications such as permanent brain damage. B. Fazekas et al. [33] found that PLWE believe the main factor preventing their seizures is their medicine (antiepileptic drugs), although the treatment is more frequently linked to side effects such as dizziness, nausea, severe memory loss, and depression. However, seizures were reported to stop completely for those adhering to their treatment. Nevertheless, shortages of AEDs, long distances to local health facilities, inadequate patient follow-up, and PLWE’s preference for traditional medicine were reported to be challenges hindering access to adequate treatment for seizure control1.

Living with epilepsy in a rural community with a diverse population can present special difficulties when trying to get medical care. People may be discouraged from seeking medical attention due to stigmatization, limited access to healthcare, and deeply held cultural beliefs. A. Molla et al. [24] provided evidence in favour of this idea, finding that even if a large number of people suffer epilepsy, not all of them receive the proper care. Most PLWE, particularly those living in rural regions, are reluctant to seek medical attention from a healthcare professional because they feel that traditional healers, traditional leaders, prophets, and community elders are the only sources of appropriate therapy. Cultural perspectives about the condition may have an impact on the health-seeking behavior of PLWE. Many PLWE choose alternative therapies over medical care in countries where epilepsy is viewed as a curse or a punishment. Similarly, B.C. Ekeh and U.E. Ekrikpo [25] found that the sociocultural beliefs such as witchcraft, demonic possession, and curses have a significant impact on health-seeking behaviour and the management that follows.

CONCLUSION / ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

Cultural beliefs, attitudes, and traditions play a crucial role in shaping treatment preferences. Even though traditional or faith-based interventions have not always been successful in reducing seizures, some with epilepsy who believe in spiritual origins for their condition prefer them. On the other hand, those who thought that medical conditions caused their seizures favoured AEDs from nearby clinics. But the difficulties they faced like the lack of AEDs made it difficult to provide them the proper care and attention.

The results emphasize the necessity of creating culturally appropriate interventions that honour the cultural values and customs of PLWE, fostering a feeling of community and encouraging the delivery of comprehensive care, all of which will enhance their quality of life.

1. Mambo R. Gaps in management and treatment of epilepsy in people with confirmed or probable neurocysticercosis (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Zambia). 2020 (https://library.adhl.africa/handle/123456789/14113).

References

1. Braga P., Hosny H., Kakooza-Mwesige A., et al. How to understand and address the cultural aspects and consequences of diagnosis of epilepsy, including stigma. Epileptic Disord. 2020; 22 (5): 531–47. https://doi.org/10.1684/epd.2020.1201.

2. Sanchez N., Kajumba M., Kalyegira J., et al. Stakeholder views of the practical and cultural barriers to epilepsy care in Uganda. Epilepsy Behav. 2021; 114 (Pt B): 107314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107314.

3. Mesraoua B., Kissani N., Deleu D., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for epilepsy treatment in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Epilepsy Res. 2021; 170: 106538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106538.

4. Ademilokun T.F., Agunbiade O.M. Aetiological explanations of epilepsy and implications on treatments options among Yoruba traditional healers in Southwest Nigeria. Afr Soc Rev. 2021; 25 (1) : 86–111.

5. Beghi E. The epidemiology of epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology. 2020; 54 (2): 185–91. https://doi.org/10.1159/000503831.

6. Nicholas A. Unlocking the hidden burden of epilepsy in Africa: understanding the challenges and harnessing opportunities for improved care. Health Sci Rep. 2023; 6 (4): e1220. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.1220.

7. Gupta N., Singh R., Seas A., et al. Epilepsy among the older population of sub-Saharan Africa: analysis of the global burden of disease database. Epilepsy Behav. 2023; 147: 109402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109402.

8. Liu J., Zhang P., Zou Q., et al. Status of epilepsy in the tropics: an overlooked perspective. Epilepsia Open. 2023; 8 (1): 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.12686.

9. Leonardi M., Martelletti P., Burstein R., et al. The World Health Organization Intersectoral Global Action Plan on epilepsy and other neurological disorders and the headache revolution: from headache burden to a global action plan for headache disorders. J Headache Pain. 2024; 25 (1): 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-023-01700-3.

10. Fawcett J., Davis S., Manford M. Further advances in epilepsy. J Neurol. 2023; 270 (11): 5655–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-023-11860-6.

11. Guekht A., Brodie M., Secco M., et al. The road to a World Health Organization global action plan on epilepsy and other neurological disorders. Epilepsia. 2021; 62 (5): 1057–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.16856.

12. Higgins A., Downes C., Varley J., et al. Supporting and empowering people with epilepsy: contribution of the Epilepsy Specialist Nurses (SENsE study). Seizure. 2019; 71: 42–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2019.06.008.

13. Dean P., O’Hara K., Brooks L., et al. Managing acute seizures: new rescue delivery option and resources to assist school nurses. NASN Sch Nurse. 2021; 36 (6): 346–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1942602X211026333.

14. Koltai D.C., Smith C.E., Cai G.Y., et al. Healthcare provider perspectives regarding epilepsy care in Uganda. Epilepsy Behav. 2021; 114 (Pt B): 107294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107294.

15. Makhado T.G., Makhado L. Perspective chapter: stigma and its impact on people living with epilepsy in rural communities. In: Carotenuto E. (Ed.) Epilepsy during the lifespan – beyond the diagnosis and new perspectives. IntechOpen; 2024: 162 pp. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.112867.

16. Deegbe D.A., Aziato L., Attiogbe A. Beliefs of people living with epilepsy in the Accra Metropolis, Ghana. Seizure. 2019; 73: 21–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2019.10.016.

17. Kaddumukasa M.N., Kaddumukasa M., Kajumba M., et al. Barriers to biomedical care for people with epilepsy in Uganda: a crosssectional study. Epilepsy Behav. 2021; 114 (Pt B): 107349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107349.

18. Chabangu Q., Maputle M.S., Lebese R.T., Makhado L. Indigenous practices for management of epilepsy by traditional healers in South Africa. Epilepsia i paroksizmal'nye sostoania / Epilepsy and Paroxysmal Conditions. 2022; 14 (3): 267–75. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2022.121.

19. Hatala A.R., Roger K. (Eds) Spiritual, religious, and faith-based practices in chronicity: an exploration of mental wellness in global context. Routledge; 2023: 300 pp.

20. De Vos A., Strydom H., Fouché C., Delport C. Research at Grass Roots: for the social sciences and human service professions. Book review. Unisa Psychologia. 2015; 29 (1): 154–8.

21. Brink H. Fundamentals of research methodology for health care professionals. 3rd ed. Cape Town: Juta; 2016: 226 pp.

22. Brink H., van der Walt C., van Rensburg G. Fundamentals of research methodology for health care professionals. 4th ed. Cape Town: Juta; 2017: 224 pp.

23. Burns N.A., Grove S.K. (Eds) The practice of nursing research: appraisal synthesis and generation of evidence. 8th ed. Philadelphia: S.W. Saunders; 2016.

24. Molla A., Mekuriaw B., Habtamu E., Mareg M. Treatment-seeking behavior towards epilepsy among rural residents in Ethiopia: a crosssectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020; 16: 433–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S240542.

25. Ekeh B.C., Ekrikpo U.E. The knowledge, attitude, and perception towards epilepsy amongst medical students in Uyo, Southern Nigeria. Adv Med. 2015; 2015: 876135. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/876135.

26. Nemathaga M., Maputle M.S., Makhado L., Mashau N.S. Views of traditional healers on collaboration with health professionals when managing epilepsy in rural areas of Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces (South Africa). Epilepsia i paroksizmal'nye sostoania / Epilepsy and Paroxysmal Conditions. 2023; 15 (3), 222–31. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2023.165.

27. Anand P., Othon G.C., Sakadi F., et al. Epilepsy and traditional healers in the Republic of Guinea: a mixed methods study. Epilepsy Behav. 2019; 92: 276–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.01.017.

28. Corneille J.S., Luke D. Spontaneous spiritual awakenings: phenomenology, altered states, individual differences, and wellbeing. Front Psychol. 2021; 12: 720579. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.720579.

29. Mokgobi M.G. Understanding traditional African healing. Afr J Phys Health Educ Recreat Dance. 2014; 20 (Suppl. 2): 24–34.

30. Wilson R., Hallard J. “God is first, MSF second, and my husband second too”. Mental health conditions and epilepsy in Liberia: understanding and healing pathways within a community-based and patient-centered care approach. 2021. Available at: https://evaluation.msf.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/Mental%20health%20conditions%20and%20epilepsy%20in%20liberia%20-%20Anthropological%20report%20final.pdf (accessed 05.08.2024).

31. Mohammed I.N., Babikir H.E. Traditional and spiritual medicine among Sudanese children with epilepsy. Sudan J Paediatr. 2013; 13 (1): 31–7.

32. Chin J.H. Epilepsy treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: closing the gap. Afr Health Sci. 2012; 12 (2): 186–92. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v12i2.17.

33. Fazekas B., Megaw B., Eade D., Kronfeld N. Insights into the real-life experiences of people living with epilepsy: a qualitative netnographic study. Epilepsy Behav. 2021; 116: 107729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107729.

About the Authors

M. NemathagaSouth Africa

Muofheni Nemathaga

University Rd, Thohoyandou 0950

M. S. Maputle

South Africa

Maria Sonto Maputle, Prof.

University Rd, Thohoyandou 0950

L. Makhado

South Africa

Lufuno Makhado, Prof.

WoS Researcher ID: I-1586-2016; Scopus Author ID: 56224434100

University Rd, Thohoyandou 0950

N. S. Mashau

South Africa

Ntsieni Stella Mashau, Assoc. Prof.

University Rd, Thohoyandou 0950

Review

For citations:

Nemathaga M., Maputle M.S., Makhado L., Mashau N.S. Experiences of people living with epilepsy regarding treatment and interventions in selected rural communities of Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces, South Africa. Epilepsy and paroxysmal conditions. 2025;17(2):161-169. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2025.216

JATS XML

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.