Scroll to:

Schoolteachers’ and pupils’ attitudes towards and misbeliefs about first aid for seizures: a scoping review

https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2025.223

Abstract

Background. Schoolteachers and pupils constitute a tremendous force of potential rescuers who may promptly respond to seizure episodes in school settings and beyond. It is important to understand their awareness and readiness towards providing first aid for seizures. A scoping review was conducted to map related evidence from international studies.

Objective: To identify and summarise current research on real-life experiences, attitudes and knowledge of schoolteachers and school pupils regarding first aid for seizures.

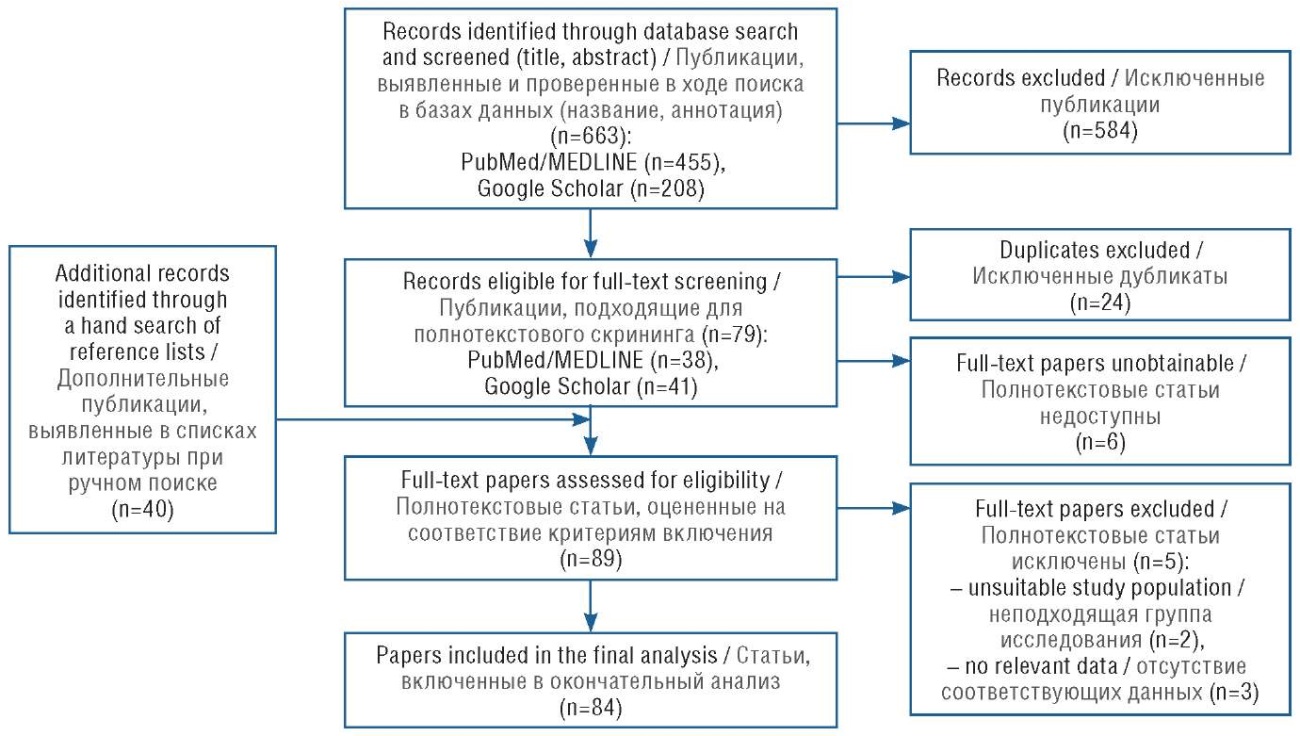

Material and methods. The search and selection of sources from PubMed/MEDLINE and Google Scholar databases was carried out in accordance with the PRISMA recommendations. All records were evaluated based on their title and abstract. After clearing from duplicates, full texts were assessed for eligibility. Bibliographies of eligible papers were hand-searched for additional relevant publications.

Results. A total of 84 survey studies conducted in 28 countries were included. Based on the collective research data, the median percentages of teachers and pupils who ever witnessed a seizure were 57.5 and 57.1, respectively. About 27.7% of teachers were bystanders to a seizure incident in a child at school. Among teachers, 22.2% attempted first aid for seizures in real life but only 9.2% received first-aid training. A large proportion of teachers and pupils considered applying measures that may cause harm to a person with seizures.

Conclusion. Schoolteachers’ and pupils’ unpreparedness to give first aid for seizures constitutes a global health concern that demands coordinated international and country-level efforts aiming at the wide implementation of high-quality education on first aid for epileptic seizures at schools.

For citations:

Birkun A.A. Schoolteachers’ and pupils’ attitudes towards and misbeliefs about first aid for seizures: a scoping review. Epilepsy and paroxysmal conditions. 2025;17(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2025.223

INTRODUCTION / ВВЕДЕНИЕ

Seizures represent one of the most common medical emergencies that put a significant burden on public health and medical resources [1]. Individuals with seizures make up approximately 4–5% of all calls to emergency medical services (EMS) [2][3] and over 1% of all emergency department visits [4]. One-fourth of all patients admitted to the emergency department with seizures require hospitalisation [4].

Seizures are associated with a risk of severe trauma and death [5][6]. About 6% of individuals with seizures who present to the emergency department have status epilepticus [4], a life-threatening condition that is characterised by a 22% overall mortality rate [1]. Early intervention from bystanders, primarily aimed at protecting the person experiencing the seizure from harm, activating EMS and administering basic life support as appropriate [7], may prevent deterioration of the victim and at times could be life-saving. Despite the importance of first aid knowledge and skills, studies show that many people have insufficient first aid competencies and harbor misconceptions about how to respond to a seizure in the real emergency situation [8].

Schools constitute a unique environment both for studying and for administering first aid for seizures. On the one hand, seizures commonly occur in school settings and are known to be one of the main reasons for school-directed EMS dispatch [9]. On the other, schoolteachers and pupils represent a tremendous contingent of potential first-aid providers. If properly trained and motivated, this multi-million global force may greatly enhance actual community response to seizures and thereby contribute to reducing associated complications and health care expenses.

As such, it is important to understand the existing beliefs and readiness towards the provision of first aid for seizures among schoolteachers and school students. Whereas studies from different countries have examined this field by means of questionnaire surveys, a holistic review of the literature concerning schoolteachers’ and pupils’ experiences, attitudes and competencies in responding to seizures is lacking. This scoping review was carried out to systematically map research evidence in this area at a global scale.

Objective: To identify and summarise current research on attitudes and knowledge of schoolteachers and school pupils regarding first aid for seizures.

MATERIAL AND METHODS / МАТЕРИАЛ И МЕТОДЫ

Protocol and registration / Протокол и регистрация

The scoping review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews guidance [10]. The review protocol was not pre-registered or published.

Information sources, search and study selection / Источники информации, поиск и отбор исследований

In February 2024, PubMed/MEDLINE and Google Scholar were searched for articles reporting results of original studies (questionnaire surveys) aimed at examining the real-life experiences, knowledge, and attitudes of schoolteachers or school students towards epilepsy and seizures (Table 1). All records were evaluated based on their title and abstract, and relevant records were imported to Zotero (Corporation for Digital Scholarship, Vienna, Virginia, USA; version 6.0.36) reference management program. After clearing from duplicates, full texts were evaluated for eligibility. Bibliographies of eligible papers were hand-searched for additional relevant publications.

Table 1. Search strategy of the scoping review

Таблица 1. Стратегия поиска исследований для включения в обзор

|

Database / База данных |

Search queries / Поисковые запросы |

|

PubMed/MEDLINE |

01. first aid[Title/Abstract] 02. school*[Title/Abstract] 03. 2004:2024[pdat] 1 and 2 and 3 |

|

Google Scholar |

01. first aid 02. school* 03. seizure* 04. epilep* 05. convuls* 06. 3 or 4 or 5 1 and 2 and 6 |

Eligibility criteria / Критерии отбора

The analysis included peer-reviewed journal papers published between 2004 and 2024, written in English and reporting one or more of the following measures: the number and/or percentage of subjects (schoolteachers or pupils) who ever witnessed a seizure, who ever provided first aid for seizures, who expressed their willingness to give first aid to a person with seizures, who supposed they know how to/able to give first aid to a person with seizures, who received training on first aid for seizures, and who wished to learn first aid for seizures, as well as the number and/or percentage of subjects who considered certain actions appropriate to help the person with seizures.

Papers were excluded if they did not contain any relevant quantitative data or involved mixed samples (e.g. included preschool and school teachers) without selective reporting of relevant quantitative data for school-level participants. From studies that evaluated the effects of educational interventions and reported data obtained before and after the intervention, only baseline measures were included.

Data collection process and data items / Процесс сбора данных и их элементы

All relevant data from eligible studies were retrieved with an author-developed data-charting form (see Supplement 11 and dataset [11]). Along with the aforementioned target measures, information about the author(s), year of publication, study geography and sample size was collected. When a paper did not report percentage values, these were calculated based on available absolute data. All data were analysed descriptively.

The review did not involve a critical appraisal of the selected papers. All data that support the findings of this research are available in Supplement 1 and in the online repository [11].

RESULTS / РЕЗУЛЬТАТЫ

Results of search and selection / Результаты поиска и отбора

The flow of the study selection is shown in Figure 1. A total of 84 unique studies conducted between 2004 and 2023 were considered eligible based on the full-text review and included in the analysis [11]. The complete bibliography of the review, comprising 84 references, is provided in Supplement 1 and in the dataset [11].

Figure 1. Flow diagram for the study selection process

Рисунок 1. Блок-схема алгоритма выбора исследований

Respondents / Респонденты

Seventy-two (85.7%) studies reported surveys of schoolteachers (total number of respondents 27,385), 13 studies (15.5%) – surveys of school students (total number of respondents 8,908). The number of respondents per study varied from 42 to 1,408 for teachers (median [interquartile range (IQR)]: 318.5 [ 204.0–489.0]) and from 70 to 1,360 for students (median [IQR]: 851.0 [ 240.0–1,066.0]).

Countries / Cтраны

The studies were carried out in 28 countries, which represent 13.7% of the 205 world’s sovereign states and 14.5% of the 193 Member states of the United Nations. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the studies by global regions and countries. According to the World Bank’s country classification [12], the surveys involved respondents from 12.0% of countries (10 of 83) with high-income economies (48.8% of studies, n=41), 7.4% of countries (4/54) with upper-middle-income economies (9.5% of studies, n=8), 18.5% of countries (10/54) with lower-middle-income economies (27.4% of studies, n=23), and 15.4% of countries (4/26) with low-income economies (14.3% of studies, n=12). The number of studies per country varied from 1 to 23, and 27.4% (n=23) of the surveys were conducted in Saudi Arabia.

Figure 2. Distribution of the reviewed studies by country and global region

Рисунок 2. Распределение исследований по странам и регионам мира

Data analysis / Анализ данных

The median percentage of teachers who ever witnessed a seizure was 57.5 (min–max: 9.3–90.8, IQR: 42.2–72.0; based on 31 studies), the median percentage of teachers who witnessed a seizure at school was 24.8 (min–max: 9.3–44.5, IQR: 17.0–29.9; 6 studies), and the median percentage of teachers who witnessed a seizure in a child at school was 27.7 (min–max: 6.1–75.5, IQR: 23.9–48.9; 13 studies). According to seven studies, the median percentage of students who ever witnessed a seizure was 57.1 (min–max: 26.1–63.3, IQR: 26.1–61.6).

Based on nine studies, the percentage of teachers who ever provided first aid for seizures varied from 0.8 to 30.0 with a median of 22.2 (IQR: 12.2–27.0), whereas the median percentage of teachers who provided first aid for seizures in a child at school was 4.4 (min–max: 2.1–13.6; according to three studies). No studies reported data on rates of provision of first aid for seizures by school students.

Based on five studies, the percentage of teachers who expressed their willingness/readiness to give first aid for seizures varied from 35.1 to 69.1 (median [IQR]: 37.3 [ 36.1–66.5]). Two studies reported a percentage of students who would try to attempt first aid in a seizure attack as 35.5 and 64.0 (median 49.8).

Twenty-six studies provided data on self-evaluated teachers’ competence in the provision of first aid for seizures. The median percentage of teachers who reported they are able to or know how to provide first aid for seizures was 37.1 (min–max: 1.6–84.2, IQR: 22.6–59.4). For students, two studies reported the percentage of respondents expressing their competence in first aid for seizures with about a 12-fold difference – 4.0% and 48.8% (median 26.4).

According to 17 studies, the median percentage of teachers who ever received training on first aid for seizures was 9.2 (min–max: 0.0–44.0, IQR: 5.3–14.1). The median percentage of teachers who indicated they wished to learn first aid for seizures amounted to 86.7 (min–max: 85.7–97.5, IQR: 86.2–93.8; based on five studies). No studies in student populations provided such data.

Multiple surveys reported results of the assessment of participants’ knowledge of the management of seizure attacks, indicating common misbeliefs concerning measures that could be taken to help a victim with ongoing seizures. The most frequently encountered misconceptions related to the provision of first aid for seizures are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The proportion of schoolteachers and pupils that considered inappropriate and potentially harmful actions for helping a victim during a seizure

Таблица 2. Доля школьных учителей и учеников, которые допускали возможность использования нецелесообразных и потенциально опасных мер при оказании помощи пострадавшему с судорогами

|

Actions / Действия |

Teachers / Школьные учителя |

Pupils / Ученики |

||||

|

Median [ IQR] / Медиана [ МКР] |

Min–Max |

Number of studies / Количество публикаций |

Median [IQR] / Медиана [МКР] |

Min–Max |

Number of studies / Количество публикаций |

|

|

Open the victim's mouth / put an object into the mouth to prevent tongue biting or "swallowing" // Открыть рот / вложить в рот пострадавшего предмет для предотвращения прикусывания или «проглатывания» языка |

40.3 [ 24.1–58.7] |

3.9–86.4 |

45 |

43.2 [ 21.9–73.2] |

16.7–85.4 |

10 |

|

Hold/restrain/tie the victim // Удерживать/ограничить/связать пострадавшего |

13.6 [ 8.9–27.5] |

2.4–73.2 |

29 |

17.1 [ 12.7–34.3] |

11.4–47.0 |

5 |

|

Let the victim smell something (a shoe, leather, cologne, onion, smoke of a struck match, etc.) / Дать пострадавшему понюхать ботинок, предмет из кожи, одеколон, лук, дым зажженной спички и т.д.) |

18.8 [ 12.8–47.2] |

5.0–74.5 |

14 |

54.2 [ n/a // н/п] |

26.5–81.9 |

2 |

|

Take the victim to a hospital once a seizure occurred / Отвезти пострадавшего с возникшими судорогами в больницу |

15.1 [ 8.9–42.6] |

3.4–93.0 |

11 |

62.3 [ n/a // н/п] |

15.7–81.6 |

3 |

|

Give medications to the victim / Дать пострадавшему лекарства |

22.1 [ 9.3–32.6] |

7.7–39.1 |

8 |

28.8 [ n/a // н/п] |

27.2–30.4 |

2 |

|

Pull the victim's tongue / Вытянуть язык пострадавшего |

10.7 [ 3.7–43.9] |

3.1–61.5 |

8 |

17.3 [ n/a // н/п] |

n/a // н/п |

1 |

|

Put food or pour drinks/liquids into the victim's mouth // Положить еду или влить напитки/жидкости в рот пострадавшему |

10.8 [ 1.1–21.8] |

0.1–28.7 |

8 |

12.8 [ n/a // н/п] |

n/a // н/п |

1 |

|

Pour/sprinkle water on the victim // Облить/обрызгать водой пострадавшего |

22.2 [ 10.2–37.8] |

3.4–58.8 |

7 |

24.7 [ 21.2–39.6] |

20.3–44.3 |

4 |

|

Perform rescue breathing and/or chest compressions // Провести искусственное дыхание и/или непрямой массаж сердца |

10.8 [ 4.0–26.5] |

2.4–28.4 |

7 |

16.8 [ n/a // н/п] |

3.6–30.0 |

2 |

|

Start praying / reading the Quran // Начать молиться / читать Коран |

4.2 [ 3.3–15.5] |

1.9–61.1 |

7 |

25.9 [ n/a // н/п] |

14.1–37.7 |

2 |

|

Take off the victim's clothes / Снять одежду с пострадавшего |

25.5 [ n/a // н/п] |

8.7–27.9 |

3 |

11.1 [ n/a // н/п] |

n/a // н/п |

1 |

|

Apply oil on the victim’s body (kernel oil, olive oil) / Нанести масло на тело пострадавшего (масло косточковых, оливковое) |

67.8 [ n/a // н/п] |

n/a // н/п |

1 |

14.7 [ n/a] |

n/a // н/п |

1 |

|

Give the victim a metal object to hold (e.g. a bunch of keys) / Дать пострадавшему подержать металлический предмет (например, связку ключей) |

n/a // н/п |

n/a // н/п |

0 |

17.4 [ 9.3–28.6] |

7.5–31.4 |

4 |

Note. IQR – interquartile range; n/a – not applicable.

Примечание. МКР – межквартильный размах; н/п – неприменимо.

DISCUSSION / ОБСУЖДЕНИЕ

The review found that the majority of schoolteachers have seen a seizure in real life, and around one-fourth have witnessed a seizure in school settings. Approximately 37% of teachers expressed their willingness to give help to a victim with seizures and the same percentage declared their ability to provide first aid for a seizure if necessary. Whereas about one out of five teachers had personally provided first aid in a seizure attack, more than 90% did not receive any training on first aid for seizures. Furthermore, a large proportion of teachers admitted the possibility of applying non-evidence-based measures when helping a victim with seizures, including nonsensical and useless but time-consuming efforts like sprinkling water over the victim or letting the victim smell shoes, and a range of dangerous actions that may cause additional harm to the victim. In particular, over 40% of teachers deemed it feasible to attempt opening the victim’s mouth and/or inserting an object into the victim’s mouth (the futile intervention that may cause dental damage or aspiration to the victim, or injury to the rescuer’s fingers) [13] and almost 14% considered it is correct to hold or tie the victim to restrain their movements during a seizure (whereas this creates the risk of musculoskeletal or soft-tissue injury to the victim).

The studies in school students are relatively uncommon. Similar to schoolteachers, most pupils have witnessed a seizure at least once in their lives, but their knowledge of first aid is inadequate as confirmed by frequently accepted misconceptions regarding methods of help in a seizure attack. Significantly more research in this extensive population is necessary to better understand pupils’ real-life experiences, beliefs and readiness towards the provision of first aid for seizures.

Being a place where a large number of people gather and spend a considerable amount of time, school represents a common scene for medical emergencies, including seizure attacks [9]. There are over 1,410 million primary and secondary education pupils [14][15], and over 73 million primary and secondary education teachers worldwide [16]. If properly prepared to give first aid, this huge force of potential rescuers may reduce the severity of injuries from seizures, prevent life-threatening complications and decrease the related burden on medical systems.

However, both schoolteachers and pupils, although being common witnesses of seizures, are mostly unprepared to correctly respond to a seizure episode. The alarming fact is that many teachers would try to give help to a victim in spite of the absence of adequate first aid competencies by applying unreasonable and potentially harmful measures. Results of the scoping review show this from an international perspective, suggesting that the problem of school unpreparedness to provide proper first aid for seizures constitutes a global health concern. Deficient knowledge of epilepsy, including limited knowledge of seizure management, among teachers from different parts of the world has been previously noted in a systematic review by C. Jones et al. [17].

The school as an educational space with well-established pedagogical practices constitutes an ideal setting for teaching first aid massively and encompassing different ages and social strata. When compared to more complex life-supporting interventions like cardiopulmonary resuscitation, first aid for managing seizures does not require advanced psychomotor or cognitive skills. Therefore, it can be effectively learnt and applied by both adults and children, including primary school pupils [18]. On the premise of adequate training, schoolteachers may serve as successful first-aid instructors [19]. Moreover, after obtaining knowledge and skills, schoolchildren may act as multipliers beyond the school settings by passing their first aid competencies to friends and relatives [20].

Taken together, current evidence suggests the necessity of active promotion of education on first aid for seizures both for schoolteachers (as part of first aid education in the workplace and to train teachers as future instructors) and for school students (as part of the school curriculum). The training should comply with the current first aid guidelines [7], be adapted to different trainees’ ages and be repeated to maintain the competencies. In order to achieve the mass effect, compulsory training on first aid for seizures at school should be endorsed on an international level. This would require a rigorous scientific statement from relevant global stakeholders as it was done by the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation for basic life support education for schoolchildren [19]. Considering a wide variety of local requirements, legislation, regulations, and financial circumstances, active participation of national governments, public health, educational, and political authorities would be required to advocate and implement mandatory training on first aid for seizures at schools.

Further research is necessary to determine optimal teaching strategies, instructional methods, and modes of delivery of training on first aid for seizures in school settings, and to develop a standardised educational framework for such training that could be recommended for worldwide implementation. More studies are also needed to evaluate the effects of educational interventions for different types of learners and further examine schoolteachers’ and pupils’ awareness, perceptions, and competencies for applying first aid.

Limitations of the review / Ограничения обзора

This work has an exploratory nature, and its results demand cautious interpretation. Limitations of the review include the literature search in two databases, analysis of English-only publications, conduction of literature search, data collection and analysis by one researcheR. It must be recognised that over a quarter of the studies were carried out in Saudi Arabia. This implies an inevitable preponderance of results from this country in the whole body of analysed researcH. Limitations inherent to questionnaire surveys and methodological heterogeneity of included studies should be acknowledged as well. Heterogeneity of analysed studies is typical for scoping reviews, and the observed diversity of the research confirms the appropriateness of the choice of scoping review methodology for this project.

CONCLUSION / ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

International research suggests the prevailing unpreparedness of schoolteachers and pupils to give first aid for seizures, and an unmet need in the first aid education at school. Common misconceptions about first aid for seizures may induce inappropriate and potentially harmful bystander actions in a real-life emergency. To enhance the readiness of schoolchildren and schoolteachers to properly respond to seizures, coordinated multi-sectorial international and country-level efforts aiming at wide implementation of high-quality education on first aid for seizures at schools are required.

1. See the electronic version of the journal: https://epilepsia.su.

References

1. Martindale J.L., Goldstein J.N., Pallin D.J. Emergency department seizure epidemiology. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011; 29 (1): 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2010.08.002.

2. Andersen M.S., Johnsen S.P., Sørensen J.N., et al. Implementing a nationwide criteria-based emergency medical dispatch system: a register-based follow-up study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013; 21: 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-21-53.

3. Møller T.P., Ersbøll A.K., Tolstrup J.S., et al. Why and when citizens call for emergency help: an observational study of 211,193 medical emergency calls. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015; 23: 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-015-0169-0.

4. Huff J.S., Morris D.L., Kothari R.U., Gibbs M.A. Emergency department management of patients with seizures: a multicenter study. Acad Emerg Med. 2001; 8 (6): 622–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb00175.x.

5. Kirby S., Sadler R.M. Injury and death as a result of seizures. Epilepsia. 1995; 36 (1): 25–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb01660.x.

6. Asiri S., Al-Otaibi A., Al Hameed M., et al. Seizure-related injuries in people with epilepsy: a cohort study from Saudi Arabia. Epilepsia Open. 2022; 7 (3): 422–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.12615.

7. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Red Cross Red Crescent Networks. International first aid resuscitation and education guidelines 2020. Available at: https://www.globalfirstaidcentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/EN_GFARC_GUIDELINES_2020.pdf (accessed 12.12.2024).

8. O’Hara K.A. First aid for seizures: the importance of education and appropriate response. J Child Neurol. 2007; 22 (5 Suppl.): 30S–7S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073807303066.

9. Knight S., Vernon D.D., Fines R.J., Dean N.P. Prehospital emergency care for children at school and nonschool locations. Pediatrics. 1999; 103 (6): e81. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.103.6.e81.

10. Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 169 (7): 467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

11. Birkun A. Dataset of original studies on schoolteachers' or pupils' reallife experiences, attitudes, and knowledge of epilepsy and seizures. Mendeley Data. 2024; V1. https://doi.org/10.17632/2ndzc6nwpx.1.

12. The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed 12.12.2024).

13. American Heart Association. Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Part 14: First aid. Circulation. 2005; 112 (24 Suppl.): IV-196–203. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166575.

14. The World Bank. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Primary education, pupils. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.PRM.ENRL (accessed 12.12.2024).

15. The World Bank. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Secondary education, pupils. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.SEC.ENRL (accessed 12.12.2024).

16. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Global report on teachers. Addressing teacher shortages. 2023. Available at: https://teachertaskforce.org/knowledge-hub/global-report-teachersaddressing-teacher-shortages-highlights (accessed 12.12.2024).

17. Jones C., Atkinson P., Helen Cross J., Reilly C. Knowledge of and attitudes towards epilepsy among teachers: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2018; 87: 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.06.044.

18. Bozkaya I.O., Arhan E., Serdaroglu A., et al. Knowledge of, perception of, and attitudes toward epilepsy of schoolchildren in Ankara and the effect of an educational program. Epilepsy Behav. 2010; 17 (1): 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.10.011.

19. Schroeder D.C., Semeraro F., Greif R., et al. KIDS SAVE LIVES: basic life support education for schoolchildren: a narrative review and scientific statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation. 2023; 147 (24): 1854–68. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001128.

20. Corrado G., Rovelli E., Beretta S., et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in high-school adolescents by distributing personal manikins. The Como-Cuore experience in the area of Como, Italy. J Cardiovasc Med. 2011; 12 (4): 249–54. https://doi.org/10.2459/JCM.0b013e328341027d.

About the Author

A. A. BirkunRussian Federation

Alexei A. Birkun, Dr. Sci. Med., Assoc. Prof.

WoS ResearcherID: R-3613-2017. Scopus Author ID: 56747693500

5/7 Lenin Blvd, Simferopol 295051;

30 October 60th Anniversary Str., Simferopol 295024

Supplementary files

|

1. Supplement 1. Data from the studies included in the review | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

Download

(65KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |

Review

For citations:

Birkun A.A. Schoolteachers’ and pupils’ attitudes towards and misbeliefs about first aid for seizures: a scoping review. Epilepsy and paroxysmal conditions. 2025;17(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2025.223

JATS XML

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.