Scroll to:

Variable clinic-EEG trajectories in male patients with PCDH19 clustering epilepsy

https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2023.156

Abstract

Background. The association between the protocadherin-19 (PCDH19) gene and epilepsy suggests that the X-linked inherited form of its pathogenic variant affects only women. Recent data has described males with somatic mosaicism, whose clinical picture is similar to the common manifestations in females.

Objective: to report on three new cases of PCDH19 clustering epilepsy in male patients.

Material and methods. Clinical data were collected from different centers through personal communication between authors, which means that the structured cohort was not tested. For all patients a next generation sequencing-based custom epilepsy gene panel and whole-exome sequencing by NextSeq 500 (Illumina Inc., USA) were performed.

Results. All patients had a previously described mosaic variants in PCDH19 gene (NM_001184880.1). According to the electroencefalographic data, all patients had a diffuse slowdown of the background rhythm, interictal regional/multiregional epileptiform activity and ictal focal pattern in the frontotemporal regions. Brain magnetic resonance imaging at the age of 3 years showed delayed myelination without focal abnormalities in 2 patients.

Conclusion. Early recognition of the above features should improve early diagnosis and long-term management of patients with epilepsy and PCDH19 mutations.

Keywords

For citations:

Dmitrenko D.V., Sharkov A.А., Domoratskaya E.А., Usoltseva A.А., Volkov I.V., Pyankov D.V. Variable clinic-EEG trajectories in male patients with PCDH19 clustering epilepsy. Epilepsy and paroxysmal conditions. 2023;15(3):260–274. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2023.156

INTRODUCTION / ВВЕДЕНИЕ

The association between the protocadherin-19 (PCDH19) gene and epilepsy suggests that its X-linked inherited pathogenic variant is asymptomatic in males and affects solely females causing the syndrome of epilepsy and mental retardation (Epilepsy Limited to Females with Intellectual Disability, EFMR) also identified as Julberg–Hellman syndrome or PCDH19 clustering epilepsy [1][2]. However, recent data have described males with mosaic pathogenic variants of the PCDH19 gene [3], displaying clinical picture similar to the common manifestations of the disease in females.

The PCDH19 gene is located on the long arm of the X chromosome (Xq22.1) encoding the protein protocadherin-19 (protocadherin-19) [4], a transmembrane protein being involved in neuronal organization and mediating cell migration. It is expressed at high level during neurogenesis in the hippocampus and cortex but found at low amount in the white matter of the brain [3][5]. Protocadherin is required for calcium-dependent cell-cell communication and adhesion. Total or partial PCDH19 gene deletion or alternation within the coding region can result in loss of function of the PCDH19 gene, leading to emergence of cells with impaired intercellular interaction.

PCDH19 expression declines postnatally but remains detectable, with the brain being its predominant site in adulthood. In addition, recent studies have highlighted the role of PCDH19 in reducing the generation of certain neurosteroid hormones such as cortisol and allopregnalonone followed by potentiated seizure susceptibility [6][7].

Pathogenic variants of the PCDH19 gene are associated with early onset of cluster epileptic seizures, often triggered by fever, cognitive impairment of varying severity, as well as behavioral disorders such as autism, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, and aggression. Clinical features may mimic Dravet syndrome (OMIM: 300088, MIM phenotype № 300088) [3].

MATERIAL AND METHODS / МАТЕРИАЛ И МЕТОДЫ

We present a report on three new cases of PCDH19 clustering epilepsy in male patients with developmental delay, drug-resistant cluster seizures, febrile seizure provocation, and early onset. The data on presented male cases were collected at diverse centers through personal communication between authors inferring that the structured patient cohort was not assessed.

For all patients, an NGS-based1 custom epilepsy gene panel and whole-exome sequencing were performed by using NextSeq 500 (Illumina Inc., USA). An in-house software pipeline was used, designed to detect single-nucleotide variants (SNVs). All gene variants and their de novo status were confirmed by Sanger sequencing in blood and buccal epithelium specimens.

Video electroencephalogram (VEEG) was performed in the state of active and passive wakefulness, sleep, as well as during functional tests for standard protocol approved by the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology (IFCN) and the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) multiple times by using non-shared equipment.

According to the HARNESS-MRI (harmonized neuro-imaging of epilepsy structural sequences magnetic resonance imaging) epilepsy protocol, brain MRI was performed multiple times for all patients by using non-shared equipment (1.5 and 3 Tesla).

Detailed clinical data were collected from patient medical records.

Ethical aspects / Этические аспекты

The case report study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association (Fortaleza, Brazil, 2013). The patients’ parents received a comprehensive information and provided written informed consent.

RESULTS / РЕЗУЛЬТАТЫ

All patients displayed similar clinical picture: onset at age ranging from 5 to 8 months, with disease course including focal attacks in clusters, sensitivity to fever, speech development disorders, neurological and behavioral abnormalities combined with mild to moderate mental retardation. At the time of manuscript preparation, all patients were receiving valproic acid as part of a polytherapy, and one patient was undergoing vagus nerve stimulation. Two patients (at the age of 7 and 11 years old, respectively) were in remission lasting for more than 1 year, and one patient (at the age of 12 years old) suffered from frequent cluster seizures [6].

Whole-exome sequencing / Полноэкзомное секвенирование

Due to the bilateral febrile provoked nature of the cluster seizures, a monogenic etiology was suspected, and an NGS-based custom epilepsy gene panel and whole-exome sequencing were performed by using NextSeq 500 (Illumina, USA). An in-house software pipeline was applied designed to detect gene SNVs. All patients had the following mosaic pattern of PCDH19 gene (NM_001184880.1) variants: Patient T. – a previously described variant chrX:99663134G>C (p.Tyr154Ter) [ PMID: 32425876]; Patient S. – a previously described variant chrX:99661914G>C (p.Pro561Arg) [ PMID: 32425876]; Patient K. – a previously described variant chrX:99663003C>G (p.Arg198Pro) [ PMID: 23712037, PMID: 26765483, PMID: 19214208]. All variants and their de novo status were confirmed by Sanger sequencing in blood and buccal epithelium specimens (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Results of Sanger sequencing

(arrows indicate the location of the identified mutation):

a – in blood; b – in buccal epithelium

Рисунок 1. Результаты секвенирования по Сэнгеру

(стрелками указано место выявленной мутации):

а – в крови; b – в буккальном эпителии

Electroencephalography / Электроэнцефалография

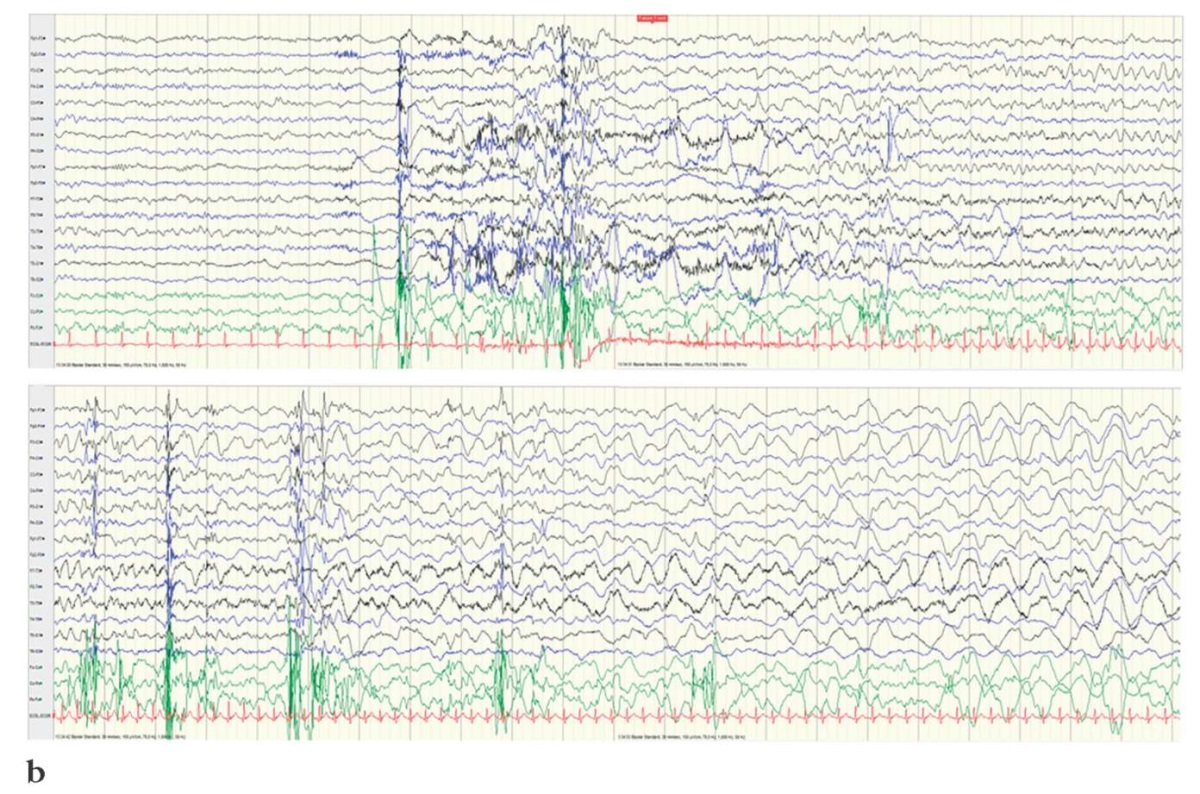

It should be underlined that both at the disease onset and during therapy the electroencephalographic (EEG) data revealed a diffuse slowdown of the background rhythm. All patients showed interictal regional/multiregional epileptiform activity and ictal focal pattern in the frontotemporal regions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Electroencephalography results

(interictal regional/multi-regional epileptiform activity

and ictal focal pattern in the frontotemporal regions):

a – Patient T.; b – Patient K.

Рисунок 2. Результаты электроэнцефалографии

(интериктальная регионарная/мультирегиональная эпилептиформная активность

и иктальный фокальный паттерн в лобно-височных областях):

а – пациент Т.; b – пациент К.

Magnetic resonance imaging / Магнитно-резонансная томография

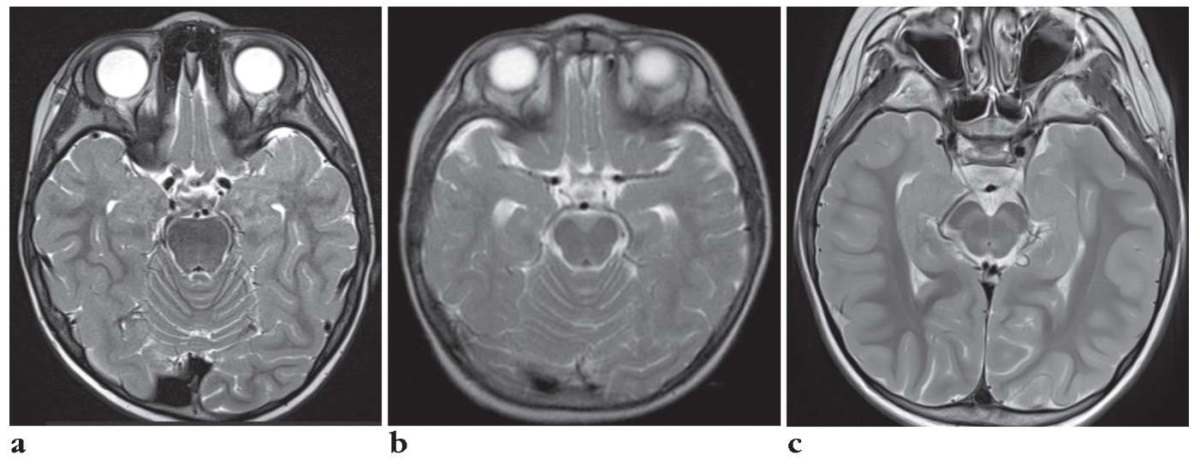

Brain MRI performed at age of 3 years old showed in two patients delayed myelination without focal abnormalities (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Magnetic resonance imaging results:

a – Patient T. (myelination disorder in the basal regions

and poles of both temporal lobes);

b – Patient S. (norm);

c – Patient K. (slight expansion of the external liquor spaces

in the anterior parts and signs of delayed myelination

of cerebral hemispheres white matter)

Рисунок 3. Результаты магнитно-резонансной томографии:

а – пациент Т. (нарушение миелинизации в базальных отделах

и полюсах обеих височных долей);

b – пациент С. (норма);

с – пациент К. (незначительное расширение наружных ликворных пространств

в передних отделах и признаки замедленной миелинизации

белого вещества полушарий головного мозга)

Detailed patients' clinical information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Detailed clinical information

Таблица 1. Подробные клинические характеристики пациентов

|

Clinical picture / |

Patient T. (Krasnoyarsk) / |

Patient S. (Novosibirsk) / |

Patient K. (Moscow) / |

|

Gender / Пол |

Male / Мужской |

Male / Мужской |

Male / Мужской |

|

Perinatal period / |

Antepartum rupture of amniotic fluid with an anhydrous interval of 14 hours, discoordination of labor / |

Discoordination of labor, emergency caesarean section, mild asphyxia / |

Antepartum rupture of amniotic fluid / |

|

Apgar score at birth / |

8/9 points // 8/9 баллов |

7/8 points // 7/8 баллов |

7/8 points // 7/8 баллов |

|

Development before the onset / |

Norm / Нормальное |

Norm / Нормальное |

With tempo-motor and psycho-speech delay / |

|

Age of onset / Возраст дебюта |

8 months / 8 мес |

7 months / 7 мес |

5 months / 5 мес |

|

Previously described variant of PCDH19 gene (NM_001184880.1) / |

chrx:99663134G>C (p.Tyr154Ter) |

chrx:99661914G>C (p.Pro561Arg) |

chrx:99663003C>G (p.Arg198Pro) |

|

Percentage of mosaic pathogenic variant / |

50% |

50% |

40% |

|

Inheritability of the pathogenic variant / |

No. De novo mutation / |

No. De novo mutation / |

No. De novo mutation / |

|

Type of onset seizure / |

Focal seizure with impaired consciousness / |

Focal, motor seizure(s) with impaired consciousness / |

Focal seizure with impaired consciousness, with a transition to bilateral tonic seizure on the background of pneumonia (low-grade fever) / |

|

Type of further seizures / |

Focal non-motor behavioral seizures with impaired consciousness, myoclonic, cluster course, bilateral tonic-clonic seizures / |

Focal motor seizures, infantile spasms / |

Focal seizures with impaired awareness (tonic (right hand placement) and hypermotor), bilateral tonic, myoclonic seizures / |

|

Febrile seizures / |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Cluster course / |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Epileptic status / |

– |

+ |

– |

|

Mental retardation / |

Moderate / Умеренная |

Moderate / Умеренная |

Moderate / Умеренная |

|

Development regression / |

– |

+ |

– |

|

Speech development / |

Motor alalia, limited understanding of speech / |

Motor alalia, limited understanding of speech / |

Motor alalia (only 2 short words), understands 30–40% of speech / |

|

Neurological abnormalities / |

Late onset of pelvic control. |

Ataxia, stereotypes / |

Walks since 1 year 2 months. By the age of 2.5 did not speak. Late onset of pelvic control (6 years). Atactic gait. Mongoloid eye shape, upturned tip of the tongue, long filter, downward angles of the mouth, cone-shaped fingertips, chubby cheeks / |

|

Psychiatric/behavioral disorders // |

Autism spectrum disorder / |

Autism spectrum disorder, aggressiveness, hyperexcitability / |

Autism spectrum disorder / |

|

Antiepileptic drugs and therapeutic effect / |

LEV: +/– (AR); ZNS: – (AR); CLN: ++/–; LEV: +/– (НР); ZNS: – (НР); CLN: ++/–; |

VPA: –; VPA + CBZ: +/–; LEV: +/–; VPA: –; VPA + CBZ: +/–; LEV: +/–; |

PHB: +/–; PHB + VPA: – (AR); PHB + VPA + CLN: +/– (AR); LTG: (AR); CBZ: – (AR); VPA + TPM + CLN: +/–; VPA + TPM + LEV (4 months): ++/–; рotassium bromide: +/–; PHT: ++/– // PHB: +/–; PHB + VPA: – (НР); PHB + VPA + CLN: +/– (НР); LTG: – (НР); CBZ: – (НР); VPA + TPM + CLN: +/–; VPA + TPM + LEV (4 мес): ++/–; бромид калия: +/–; PHT: ++/– |

|

Current therapy / Текущая терапия |

VPA + OXC, VPA + OXC, |

VPA + LEV + nitrazepam / |

LEV + VPA + TPM + PHT |

|

Current age and seizure frequency / |

12 years old, clusters once in 10–12 days with 15–17 attacks in a cluster (1–2 days) / |

11 years old, no seizures for 3 years / |

7 years old, remission since March 2020 / |

|

EEG after the onset / |

Main background activity 2–4 Hz, interictal epileptiform activity in the temporal lobe of brain right hemisphere / |

Main background activity 2–4 Hz, regional slowing down in the frontal-central-temporal regions, ictal regional deceleration in the right temporal leads with the appearance of diffuse peak-wave activity / |

Diffuse slowing down of the background rhythm with a predominance of theta activity, with smooth zonal differences. Atypical vertices in the initial dream. No epileptiform activity registered / |

|

Intermediate EEG / |

Diffuse rhythmic theta slowdown of the background rhythm. The main rhythm is not clearly differentiated. Multiregional interictal epileptiform activity was registered in the state of wakefulness and superficial stages of sleep: in the left frontotemporal regions, the right frontotemporal region, bifrontal-central, bifrontal-central-temporal, diffuse flashes with a pronounced amplitude accent in the frontal regions. A focal seizure with hypermotor manifestations was registered, with a transition to an asymmetric tonic seizure and bilateral tonic-clonic seizures (ictal pattern from the left frontotemporal regions) / |

Hypsarrhythmia / Гипсаритмия |

Diffuse rhythmic theta slowdown of the background rhythm. The basic rhythm is not clearly differentiated. Sleep is structured in stages, physiological sleep patterns are presented satisfactorily. During sleep, bifrontal adhesions (involving the anterior vertex regions) were quite often recorded, the morphology of which, in most cases, satisfies the EEG pattern of “atypical vertex waves”. However, in some cases, graphoelements of the “peak-slow wave” type were recorded, which is indicative of epileptiform activity / |

|

Last EEG / Последняя ЭЭГ |

Diffuse delta-range flashes, generalized discharges of grouped peak-slow wave complexes with bifrontal dominance / |

No epiactivity / |

Transient regional slowdown in left hemisphere temporal lobe. Ictal pattern – regional slowing F3–C3–T3 (focal seizure with hypermotor manifestations, dystonia in the right hand, impaired consciousness) / |

|

MRI result and age / |

3 years, myelination disorder in the basal regions and poles of both temporal lobes / |

5 years, 3 T, variant of the norm / 5 лет, 3 Тл, вариант нормы |

3 years, slight expansion of the external liquor spaces in the anterior parts and signs of delayed myelination of cerebral hemispheres white matter / |

|

Additionally / Дополнительно |

Thin layer chromatography of blood acids is normal; phenylalanine is normal; tandem mass spectrometry mass spectrometry – hereditary aciduria and mitochondrial diseases were not identified; aCGH – no pathogenic microstructural rearrangements were identified [1] / |

– |

Chromosomal microarray analysis extended – no pathology. SCN1A targeted sequencing – no significant variants / |

Note. EEG – electroencephalography; MRI – magnetic resonance imaging; LEV – levetiracetam; ZNS – zonisamide; CLN – clonazepam; RUF – rufinamide; OXC – oxcarbazepine; LTG – lamotrigine; VPA – valproic acid; TPM – topiramate; CBZ – carbamazepine; PHT – phenytoin; PHB – phenobarbital; LAC – lacosamide; AR – adverse reactions; VNS – vagus nerve stimulation; "–" – no effect; "+/–" – weak effect; "++/–" – medium effect; aCGH – array comparative genomic hybridization.

Примечание. ЭЭГ – электроэнцефалография; МРТ – магнитно-резонансная томография; LEV (англ. levetiracetam) – леветирацетам; ZNS (англ. zonisamide) – зонисамид; CLN (англ. clonazepam) – клоназепам; RUF (англ. rufinamide) – руфинамид; OXC (англ. oxcarbazepine) – окскарбазепин; LTG (англ. lamotrigine) – ламотриджин; VPA (англ. valproic acid) – вальпроевая кислота; TPM (англ. topiramate) – топирамат; CBZ (англ. carbamazepine) – карбамазепин; PHT (англ. phenytoin) – фенитоин; PHB (англ. phenobarbital) – фенобарбитал; LCM (англ. lacosamide) – лакосамид; НР – неблагоприятная реакция; VNS (англ. vagus nerve stimulation) – стимуляция блуждающего нерва; «–» – без эффекта; «+/–» – слабый эффект; «++/–» – средний эффект; aCGH (англ. array comparative genomic hybridization) – массив сравнительной геномной гибридизации.

DISCUSSION / ОБСУЖДЕНИЕ

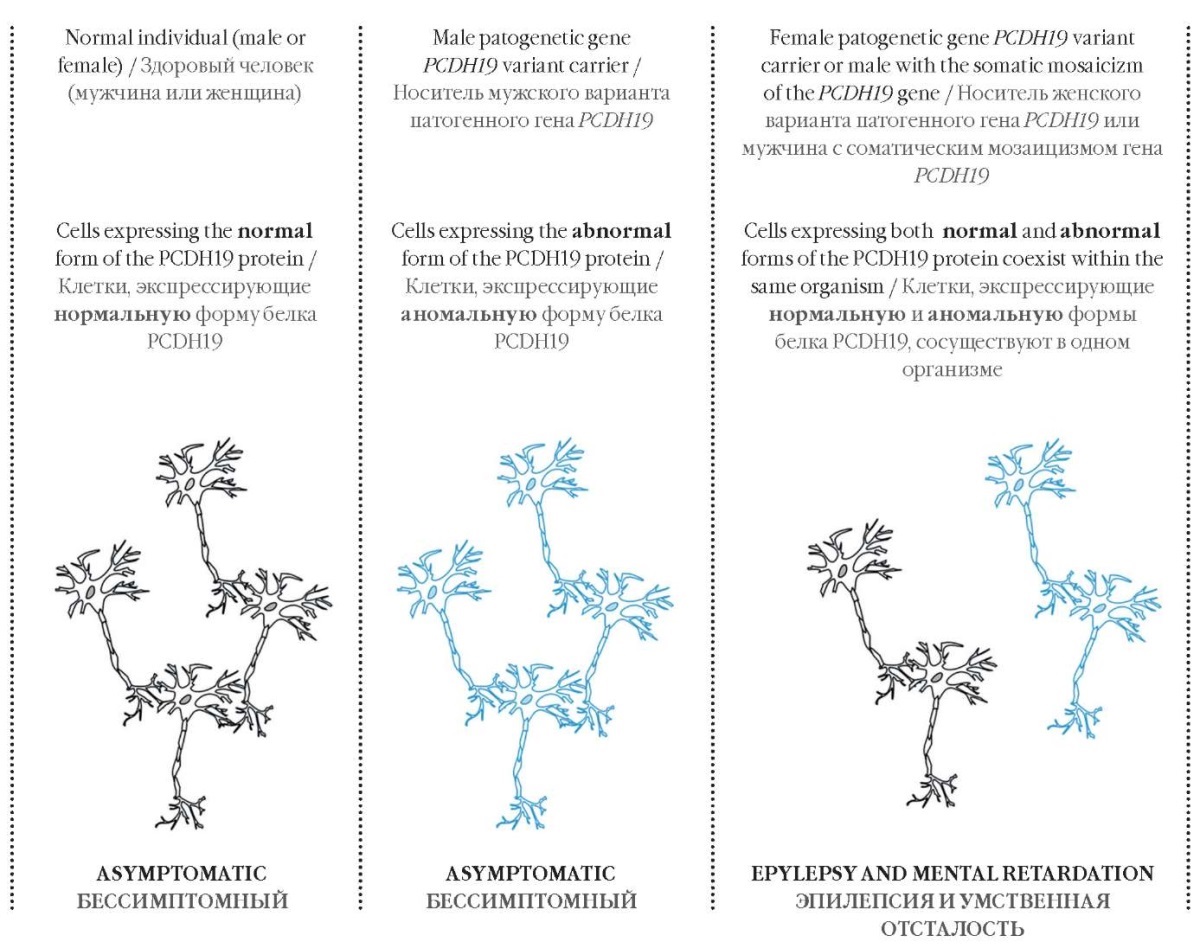

A pathogenic variant of the PCDH19 gene was first described in 2009 in a male with somatic mosaicism. This discovery inspired to propose a theory for the disease pathogenesis: PCDH19 clustering epilepsy occurs when two distinct cell populations coexist within the same host (cells expressing normal and aberrant PCDH19 protein counterparts) that putatively disrupts intercellular communication (Fig. 4). It may account for why heterozygous carriers (females) are susceptible to the disease onset, whereas homozygotes (men) become ill only in the case of somatic mosaicism [3].

Figure 4. The pathogenesis of the PCDH19 clustering epilepsy

Рисунок 4. Патогенез кластерной эпилепсии, связанной с мутацией в гене PCDH19

PCDH19 promotes cell adhesion specificity in a combinatorial manner so that mosaic PCDH19 expression in heterozygous female mice results in targeted sorting between wild-type PCDH19-positive and -negative cells in developing cortex that correlates with altered neural activity. Complete deletion of the PCDH19 gene in heterozygous mice removes abnormal cell sorting and restores normal network activity [8].

Randomly inactivated X chromosome in females results in emergence of somatic mosaicism due to a mixture of both normal and abnormal protocadherin expressing-cell types. Such somatic mosaicism elicits alterations in interplay between both cell types followed by dysfunctional cell sorting and synaptogenesis. In contrast, males with hemizygous mutations generate only one cell type bearing certain protocadherin deficient subclass, but remain asymptomatic due to the lack of cellular intervention. However, for males with somatic mosaicism of the PCDH19 gene, a phenotype resembling that of heterozygous females is typical that results from altered cellular crosstalk between both distinct cell types [7][9–14].

Both girls and boys display similar clinical picture of epilepsy associated with the PCDH19 gene mutation (girls clustering epilepsy PCDH19-GCE) that includes early onset of the disease (at the age of 6–36 months, on average at the age of 4–18 months); generalized tonic-clonic or/and focal epileptic seizures, often provoked by fever; short seizures with a cluster course; and pharmacoresistance [1][2][15][16]. The disease is featured with a progressive course along with rising seizure rate and seizure number per a cluster, gradually developing mental retardation of varying severity [17–19]. Three clinical stages of PCDH19-GCE have been identified: clusters of seizures without fever within the first 2 years of life, clusters of seizures during fever between age of 2 and 10 years old, and rare epileptic seizures and behavioral disturbances observed at age over 10 years old. We registered and described clusters of epileptic seizures in patients under the age of 2 years old [20].

Patients with PCDH19-GCE may be also observed to show stereotypical movements, hyperreflexia, autism spectrum disorders, and other neuropsychiatric disorders with aggression, obsessive disorders, schizophrenia, hysteria, depression, a tendency to self-harm as well as attention deficit in case of hyperactivity disorder [14][18][21].

The rate of seizures in PCDH19-GCE girls often declines during puberty potentially due to hormonal changes [17][20][22–24]. However, an age-related decrease in seizure rate was reported in the patients examined as well as some other identified male patients. Therefore, this tendency seems unlikely to occur solely in females being associated with female hormones [6]. N. Higurashi et al. (2015) suggest that remission of seizures in adolescence occurs due to maturation of the blood-brain barrier [25].

The PCDH19 protein is expressed stronger in endothelial cells in the central nervous system than in other organs. N. Higurashi et al. (2015) consider that seizures, resulting from PCDH19 gene mutation usually occur in the limbic region located closer to the periventricular regions [25].

EEG often shows focal or multifocal epileptiform changes and background slowdown [26]. Registration of focal and multifocal activity based on EEG data alerts researchers to the presence of structural changes in patient brain. Four out of five girls with focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) were recorded to have multifocal changes, and one girl – diffuse changes without focal activity [27].

MRI data often reveal a variant of the normal pattern. In addition, various cortical malformations have been identified in patients with epilepsy associated with PCDH19-GCE [8]. Study by N. Trivisano et al. (2018) detected FCD in 4% patients, with 10% of them suspected to have same diagnosis [22].

Similar data were observed in a series of studies: in 3 patients reported by Y. Tan et al. (2018) [8]; in 2 patients – by A. Liu et al. (2019) [15]; and in 6 to 9 patients – by I.M. de Lange et al. (2017) [3]. A dilated perivascular and subarachnoid spaces were found in 2 out of 9 observed patients reported in the study by I.M. Lange et al. (2017) [3] similar to MRI changes in found by us in Patient K.

Analysis of MRI images reveals cortical sulcus abnormalities in 4 girls with PCDH19-GCE [23]. The patients had various cerebral cortex abnormalities, including dysplasia of the bottom of the sulcus, abnormal cortex fold, thickened cortex as well as blurred transition between gray and white matter [8][23]. M. Kurian et al. (2018) described an improved seizure control in 2 patients after FCD resection [27].

The coincidence between pathogenic PCDH19 variants and cortical malformations including FCD remains controversial. FCD may not occur accidentally and could be accounted for by a putative role that PCDH19 might play in neuronal migration demonstrated in some animals or in vitro in human pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons [5][11][27][28].

However, the process of abnormal cell sorting and its potential to cause the above alterations have not yet been well understood. The variability of the abnormalities is consistent with the random X-chromosome inactivation as well as the phenotypes observed in patients with PCDH19-GCE [8][29][30].

It is likely that males with about 50% brain mosaicism intrinsically bearing high level of cellular interference may display a more severe clinical picture than males with a lower or higher percentage of mosaicism [3]. The high or low percentage of mosaicism resembles that of skewed X-inactivation in female patients, which has also been thought to result in a milder phenotype [26][30], which, however, revealed no clear correlation [7][21][25][31].

The generation of differential adhesion affinity in neuronal progenitor cells induced by mosaic PCDH19 expression appears underlie the essential cellular mechanism responsible for the unique X-linked inheritance for PCDH19-GCE. Even the lack of PCDH19 observed in hemizygous males results in no emergence of incompatible adhesion specificity that allows for normal position of neuronal progenitor cells and neural activity. An abnormal rearrangement of neuronal progenitor cells in the nascent cortex of the heterozygous brain points that at least some of their neuronal descendants may be located aberrantly, regardless of whether they support postpartum PCDH19 expression. Such reorganization may disrupt functional boundaries of the cortex and affect links between cortical and subcortical regions [8].

If the entire cerebral cortex were to undergo segregation, it might likely lead to aberrant organization of the functional cortical columns. In case an abnormal cell sorting occurs throughout the cortex, a difference in neuronal architecture between humans and mice could contribute to a more severe phenotype observed in PCDH19-GCE patients [8].

In addition, the identification of altered cortical sulcus suggests that aberrant cell sorting may cause diverse morphological phenotypes in the gyrencephalic vs. lissencephalic brain. The cortical fold of the human brain largely results from varying proliferation of the basal radial glia cells comprising a small proportion of progenitor cells in the lissencephalic vs. gyrencephalic brain [8][29][32]. The overgrowth of the basal radial glia cells triggers formation of “wedges” emerging from cell dense areas that ultimately accounts for brain fold. Segregation within basal radial glial cells in developing human brain may result in abnormal development due to improper “wedge” formation [8].

On the other hand, neurodevelopmental disorders associated with mutations in other non-clustered members belonging to the protocadherin family (NC PCDH) may be caused by impaired cell adhesion affinity [8][33][34]. It is likely that mosaic disruption of adhesion specificity occurs via a process other than X-inactivation primarily due to random monoallelic NC PCDH expression [35]. Individuals with a heterozygous germline mutation in certain autosomal NC PCDHs may bear some cells expressing either a functional or a non-functional allele resulting in impaired adhesion specificity. The proportion of cells affected by random monoallelic NC PCDH expression is likely to affect the penetrance or expressivity of any resulting phenotype [8].

The in vivo interaction of the relevant adhesion affinities for each of such closely related families of NC PCDH proteins can lead to diverse outcomes. The coordinated expression of grouped protocadherins is believed to result in repulsion involved in neuron self-recognition [8][36][37]. On the other hand, it has been shown that NC PCDH-expressing cells are able to selectively interact in vivo. Given the multi-layered and overlapping pattern of NC PCDH expression throughout development, it seems likely that this property might regulate spatial arrangement of neuronal cell progenitors to be potentially exploited during the morphogenesis of other organs [8][38].

Thus, the loss of PCDH19 is associated, e.g., with altered columnar organization and elevated cell proliferation in the optical membrane [24][27] additionally triggering brain hyperexcitability in zebrafish models [39]. Although no major morphological defects were observed in the mutant brain, the loss of mouse PCDH19 similarly enhances neuronal cell migration [27][28].

Cerebral cortical malformations comprise an important cause of developmental abnormalities and PCDH19-GCE, so that some of them are related to defects in specific genes [22v40]. When FCD emerges, the co-occurrence of pathogenic variants of SCN1A is not considered to account for the overall clinical picture, but the loss or dysfunction of the relevant protein, action of susceptibility factors and genetic modifiers of phenotypic expression may collectively play a certain role [41]. In addition, MRI signs related to FCD were detected in patients with other monogenic forms of epileptic encephalopathies [42]. Such associations discussed here by us highlight a need for further study to provide deeper insights into underlying mechanisms and, consequently, examination and clinical management of such patients [43–45].

CONCLUSION / ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

Early recognition of the above features should improve early diagnostics and long-term management of patients with epilepsy coupled to PCDH19 mutations. In this context, MRI plays a unique role in establishing the phenotypic signature of such associations in vivo. It is important to note that a specialized assessment is required prior to drawing a conclusion that no structural changes in the brain take place. Stereotypical focal epileptic seizures observed in such patient cohort require exclusion of structural changes in the brain as well as performing pre-surgical examination.

1. NGS – next generation sequencing.

References

1. Kolc K.L., Sadleir L.G., Scheffer I.E., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 271 PCDH19-variant individuals: identifies psychiatric comorbidities, and association of seizure onset and disease severity. Mol Psychiatry. 2019; 24 (2): 241–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0066-9.

2. Mukhin K.Yu., Pylaeva O.A., Dolinina A.F., et al. Epilepsy caused by PCDH19 gene mutation: a review of literature and the authors’ observations. Russian Journal of Child Neurology. 2016; 2 (11): 26–32 (in Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17650/2073-8803-2016-11-2-26-32.

3. de Lange I.M., Rump P., Neuteboom R., et al. Male patients affected by mosaic PCDH19 mutations: five new cases. Neurogenetics. 2017; 18 (3): 147–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10048-017-0517-5.

4. Dibbens L.M., Tarpey P.S., Hynes K., et al. X-linked protocadherin 19 mutations cause female-limited epilepsy and cognitive impairment. Nat Genet. 2008; 40 (6): 776–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.149.

5. Compagnucci C., Petrini S., Higuraschi N., et al. Characterizing PCDH19 in human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and iPSC-derived developing neurons: emerging role of a protein involved in controlling polarity during neurogenesis. Oncotarget. 2015; 6 (29):26804–13. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5757.

6. Trivisano M., Lucchi C., Rustichelli C., et al. Reduced steroidogenesis in patients with PCDH19-female limited epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2017; 58 (6): e91–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13772.

7. Thiffault I., Farrow E., Smith L., et al. PCDH19-related epileptic encephalopathy in a male mosaic for a truncating variant. Am J Med Genet A. 2016; 170 (6): 1585–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.37617.

8. Pederick D., Richards K.L., Piltz S.G., et al. Abnormal cell sorting underlies the unique X-linked inheritance of PCDH19 epilepsy. Neuron. 2018; 97 (1): 59–66.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.12.005.

9. Dibbens L.M., Kneen R., Bayly M., et al. Recurrence risk of epilepsy and mental retardation in females due to parental mosaicism of PCDH19 mutations. Neurology. 2011; 76 (17): 1514–9. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318217e7b6.

10. Terracciano A., Specchio N., Dara F., et al. Somatic mosaicism of PCDH19 mutation in a family with low-penetrance EFMR. Neurogenetics. 2012; 13 (4): 341–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10048-012-0342-9.

11. Cooper S.R., Jontes J.D., Sotomayor M. Structural determinants of adhesion by Protocadherin-19 and implications for its role in epilepsy. Elife. 2016; 5: e18529. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18529.

12. Gerosa L., Francolini M., Bassani S., Passafaro M. The role of protocadherin 19 (PCDH19) in neurodevelopment and in the pathophysiology of early infantile epileptic encephalopathy-9 (EIEE9). Dev Neurobiol. 2019; 79 (1): 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/dneu.22654.

13. Terracciano A., Trivisano M., Cusmai R., et al. PCDH19-related epilepsy in two mosaic male patients. Epilepsia. 2016; 57 (3): e51–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13295.

14. Hung L.Y., Subramaniam S.R., Tong T.Y.T., et al. X-chromosome inactivation and PCDH19-associated epileptic encephalopathy: a novel PCDH19 variant in a Chinese family. Clin Chim Acta. 2021; 521: 285–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2021.07.023.

15. Liu A., Yang X., Yang X., et al. Mosaicism and incomplete penetrance of PCDH19 mutations. Med Genet. 2019; 56 (2): 81–8. https://doi. org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-105235.

16. Kolc K.L., Sadleir L.G., Depienne C., et al. A standardized patientcentered characterization of the phenotypic spectrum of PCDH19 girls clustering epilepsy. Transl Psychiatry. 2020; 10 (1): 127. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-0803-0.

17. Pham D.H., Tan C.C., Homan C.C., et al. Protocadherin 19 (PCDH19) interacts with paraspeckle protein NONO to co-regulate gene expression with estrogen receptor alpha (ERa). Hum Mol Genet. 2017; 26 (11): 2042–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddx094.

18. Stevenson R.E., Holden K.R., Rogers R.C., Schwartz C.E. Seizures and X-linked intellectual disability. Eur J Med Genet. 2012; 55 (5): 307–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2012.01.017.

19. Kozina A.A., Okuneva E.G., Baryshnikova N.V., et al. Two novel PCDH19 mutations in Russian patients with epilepsy with intellectual disability limited to females: a case report. BMC Med Genet. 2020; 21 (1): 209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-020-01119-6.

20. Chemaly N., Losito E., Pinard J.M., et al. Early and long-term electroclinical features of patients with epilepsy and PCDH19 mutation. Epileptic Disord. 2018; 20 (6): 457–67. https://doi.org/10.1684/ epd.2018.1009.

21. Tan Y., Hou M., Ma S., et al. Chinese cases of early infantile epileptic encephalopathy: a novel mutation in the PCDH19 gene was proved in a mosaic male – case report. BMC Med Genet. 2018; 19 (1): 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-018-0621-x.

22. Trivisano N., Pietrafusa A., Terracciano А., et al. Defining the electroclinical phenotype and outcome of PCDH19-related epilepsy: a multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2018; 59 (12): 2260–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.14600.

23. Scheffer I.E., Turner S.J., Dibbens L.M., et al. Epilepsy and mental retardation limited to females: an under-recognized disorder. Brain. 2008; 131 (4): 918–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awm338.

24. Cooper S.R., Emond M.R., Duy P.Q., et al. Protocadherins control the modular assembly of neuronal columns in the zebrafish optic tectum. J Cell Biol. 2015; 211 (4): 807–14. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201507108.

25. Higurashi N., Takahashi Y., Kashimada A., et al. Immediate suppression of seizure clusters by corticosteroids in PCDH19 female epilepsy. Seizure. 2015; 27: 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2015.02.006.

26. Specchio N., Marini C., Terracciano A., et al. Spectrum of phenotypes in female patients with epilepsy due to protocadherin 19 mutations. Epilepsia. 2011; 52 (7): 1251–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.15281167.2011.03063.x.

27. Kurian M., Korff C.M., Ranza E., et al. Focal cortical malformations in children with early infantile epilepsy and PCDH19 mutations: case report. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018; 60 (1): 100–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13595.

28. Pederick D.T., Homan C.C., Jaehne E.J., et al. PCDH19 Loss-of-function increases neuronal migration in vitro but is dispensable for brain development in mice. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 26765. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26765.

29. Borghi R., Magliocca V., Petrini S., et al. Dissecting the role of PCDH19 in clustering epilepsy by exploiting patient-specific models of neurogenesis. Clin Med. 2021; 10 (13): 2754. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10132754.

30. Depienne C., Trouillard O., Bouteiller D., et al. Mutations and deletions in PCDH19 account for various familial or isolated epilepsies in females. Hum Mutat. 2011; 32 (1): 1959–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.21373.

31. Leonardi E., Sartori S., Vecchi M., et al. Identification of four novel PCDH19 mutations and prediction of their functional impact. Ann Hum Genet. 2014; 78 (6): 389–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/ahg.12082.

32. Wang X., Tsai J.W., LaMonica B., Kriegstein A.R. A new subtype of progenitor cell in the mouse embryonic neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2011; 14 (5): 555–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2807.

33. Ishizuka K., Kimura H., Wang C., et al. Investigation of rare singlenucleotide PCDH15 variants in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. PLoS One. 2016, 11 (4): e0153224. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153224.

34. Morrow E.M., Yoo S.Y., Flavell S.W., et al. Identifying autism loci and genes by tracing recent shared ancestor. Science. 2008; 321 (5886): 218–23. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1157657.

35. Savova V., Patsenker J., Vigneau S., Gimelbrant A.A. dbMAE: the database of autosomal monoallelic expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44 (D1): D753–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1106.

36. Rubinstein R., Thu C.A., Goodman K.M., et al. Molecular logic of neuronal self-recognition through protocadherin domain interactions. Cell. 2015: 163 (3): 629–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.026.

37. Thu C.A., Chen W.V., Rubinstein R., et al. Single-cell identity generated by combinatorial homophilic interactions between α, β, and γ protocadherins. Cell. 2014; 158 (5): 1045–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.012.

38. Berezhanskaya S.B., Lukyanova E.A., Abduragimova M.K. Molecular and genetic predictors of endothelial dysfunction and impairment of angioand neurogenesis in the perinatal period. Siberian Medical Review. 2021; 5: 14–23 (in Russ.). https://doi.org/10.20333/25000136-2021-5-14-23.

39. Robens B.K., Yang X., McGraw C.M., et al. Mosaic and non-mosaic protocadherin 19 mutation leads to neuronal hyperexcitability in zebrafish. Neurobiol Dis. 2022; 169: 105738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105738.

40. Guerrini R., Marini C. Genetic malformations of cortical development. Exp Brain Res. 2006; 173 (2): 322–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221006-0501-z.

41. Barba C., Parrini E., Coras R., et al. Co-occurring malformations of cortical development and SCN1A gene mutations. Epilepsia. 2014; 55 (7): 1009–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12658.

42. Sharkov A., Dulac O., Gataullina S. STXBP1 germline mutation and focal cortical dysplasia. Epileptic Disord. 2021; 23 (1): 143–7. https://doi.org/10.1684/epd.2021.1245.

43. Baulac S., Ishida S., Marsan E., et al. Familial focal epilepsy with focal cortical dysplasia due to DEPDC5 mutations. Ann Neurol. 2015; 77 (4): 675–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24368.

44. Weckhuysen S., Holmgren P., Hendrickx R., et al. Reduction of seizure frequency after epilepsy surgery in a patient with STXBP1 encephalopathy and clinical description of six novel mutation carriers. Epilepsia. 2013; 54 (5): e74–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12124.

45. Chemaly N., Losito E., Pinard J.M., et al. Early and long-term electroclinical features of patients with epilepsy and PCDH19 mutation. Epileptic Disord. 2018; 20 (6): 457–67. https://doi.org/10.1684/epd.2018.1009.

About the Authors

D. V. DmitrenkoRussian Federation

Diana V. Dmitrenko – Dr. Med. Sc., Chief of Chair of Medical Genetics and Clinical Neurophysiology, Institute of Postgraduate Education, Head of Laboratory of Medical Genetics, Head of Neurological Center, University Clinic

WoS ResearcherID: H-7787-2016

1 Partizan Zheleznyak Str., Krasnoyarsk 660022

A. А. Sharkov

Russian Federation

Artem A. Sharkov – Researcher, Department of Neuropsychiatry and Epileptology; Head of Neurology Department

1 Ostrovityanov Str., Moscow 117997

8 corp. 5 Podolskoe Ave., Moscow 115093

E. А. Domoratskaya

Russian Federation

Ekaterina A. Domoratskaya – Resident, Chair of Medical Genetics

2/1 bldg 1 Barrikadnaya Str., Moscow 125993

A. А. Usoltseva

Russian Federation

Anna A. Usoltseva – Postgraduate, Chair of Medical Genetics and Clinical Neurophysiology, Institute of Professional Education

Scopus Author ID: 57210425243

1 Partizan Zheleznyak Str., Krasnoyarsk 660022

I. V. Volkov

Russian Federation

Iosif V. Volkov – MD, PhD, Neurologist-Epileptologist

5 Vokzalnaya Magistral Str., Novosibirsk 630096

D. V. Pyankov

Russian Federation

Denis V. Pyankov – Head of Laboratory

Moscow

Review

For citations:

Dmitrenko D.V., Sharkov A.А., Domoratskaya E.А., Usoltseva A.А., Volkov I.V., Pyankov D.V. Variable clinic-EEG trajectories in male patients with PCDH19 clustering epilepsy. Epilepsy and paroxysmal conditions. 2023;15(3):260–274. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2023.156

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.