Scroll to:

Living with epilepsy: patient knowledge and psychosocial impact

https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2024.166

Abstract

Background. People living with epilepsy (PLWE) often face psychological comorbidities and social challenges due to low levels of knowledge and awareness about epilepsy, as well as personal experiences with the condition. This can result in a low quality of life for PLWE.

Objective: to investigate the psychosocial impact of epilepsy on patients residing in rural regions of South Africa (Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces).

Material and methods. A non-experimental quantitative research was conducted, which involved 162 respondents living with epilepsy. Most were males, and the majority were between 18 and 35 years old in both provinces combined. The participants were offered a questionnaire divided into three sections comprising sociodemographic aspects, questions that assessed knowledge, and questions on the psychosocial impact of epilepsy.

Results. I t was shown that while PLWE have a solid understanding of epilepsy as a medical condition, they may not fully comprehend its effects on daily life. For example, many respondents felt shameful after having a seizure and difficulties in forming relationships, and a significant proportion stated that they were never married because of epilepsy. The study highlights the significant psychosocial impact of epilepsy on PLWE, including depression, difficulties in forming and maintaining social connections, and a lack of marital experience.

Conclusion. To improve PLWE’s quality of life, the psychological help is recommended through healthcare facilities or local support groups.

For citations:

Musekwa O.P., Makhado L. Living with epilepsy: patient knowledge and psychosocial impact. Epilepsy and paroxysmal conditions. 2024;16(1):33-44. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2024.166

INTRODUCTION / ВВЕДЕНИЕ

Epilepsy is a common neurological disease that can affect anyone. Beghi [1] shows that the prevalence of epilepsy amongst low-to-middle-income countries is 8.75 per 1000. In addition, epilepsy is more common in the youngest and oldest age groups (affecting 86 people out of 100,000 per year), 31 out of 100,000 people aged 30–59 years are affected by epilepsy, and approximately 180 people out of 100,000 that are over the age of 85 [1]. Y. Hu et al. [2] show that both men and women can have epilepsy, although men are more likely to suffer from it than women. Thus, epilepsy is a condition that can affect anyone and causes disease burden [3][4].

Like any other disease, epilepsy impacts its patients’ lives in one way or another. It was found that people living with epilepsy (PLWE) experience a low quality of life [5][6]. Low quality of life and experiences of living with epilepsy consequently leave PLWE with some psychosocial comorbidities. This includes feeling shame, stigma, and discrimination, being stressed and depressed, experiencing anxiety, and dropping out of school [7–11]. Despite the recommendation of providing psychological support for PLWE, it is essential to note that intentional epilepsy education and awareness are also crucial in reducing the impact of epilepsy. However, this has not yet been widely implemented [11–13].

Studies have been conducted regarding epilepsy awareness and knowledge among health providers and community members [14–17], and some focused on the psychological impact of epilepsy [18–20]. However, not many studies have focused on the knowledge of the disease and the psychosocial impact on epilepsy patients themselves. For this reason, this study investigated PLWE’s level of knowledge about epilepsy as well as its effects.

Objective: to investigate the psychosocial impact of epilepsy on patients residing in rural regions of South Africa (Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces).

MATERIAL AND METHODS / МАТЕРИАЛ И МЕТОДЫ

A non-experimental quantitative research study was performed.

Population and sampling / Популяция и выборка

The population of interest included PLWE who reside in rural Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces. Trained home-based carers (HBCs) selected respondents who were already acquainted within the villages. Total population sampling (based on clinic records and knowledge of HBCs) from the villages was applied. From all known PLWE, 162 respondents consented to participate in the study. Only individuals above 18 years of age diagnosed with epilepsy were eligible for participation.

Data collection / Сбор данных

HBCs administrated the questionnaire for any respondent who needed help to write or requested assistance. However, some questionnaires were self-administered. The questionnaire was divided into three sections:

- section one comprised sociodemographic questions (n=8);

- section two comprised of questions that assessed knowledge (n=9);

- section three had questions on the psychosocial impact of epilepsy (n=22).

Data analysis / Анализ данных

An ordinal scale was used to analyze psychosocial impact, and Likert scales for knowledge held and some psychosocial impact and experiences. Analysis was done using Statistical Package of Social Sciences Software version 26.0 (SPSS, USA). This study tool was piloted on 10 PLWE who were later not included. The researchers employed cross-tabulation and Chi-Square analysis to compare demographic characteristics between Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces. Additionally, the researchers utilized the same method alongside Phi and Cramer's V to assess and quantify the disparities in the knowledge of PLWE and the psychosocial impact of epilepsy across these provinces. This approach was instrumental in identifying the differences and evaluating the strength of the associations between the variables in the two regions.

Ethical aspects / Этические аспекты

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Venda (SHS/20/PSYCH/12/2710, approved 30 October 2020). Before data collection, participants were asked to sign a consent form and received a study information sheet (translated into their language) to keep.

RESULTS / РЕЗУЛЬТАТЫ

Sociodemographic data / Социально-демографические данные

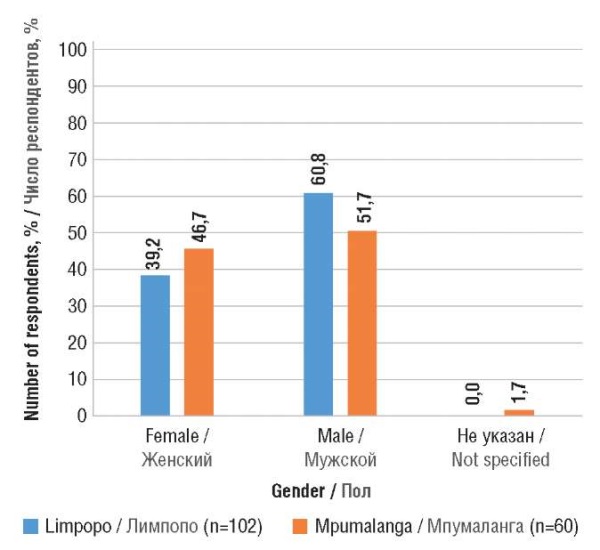

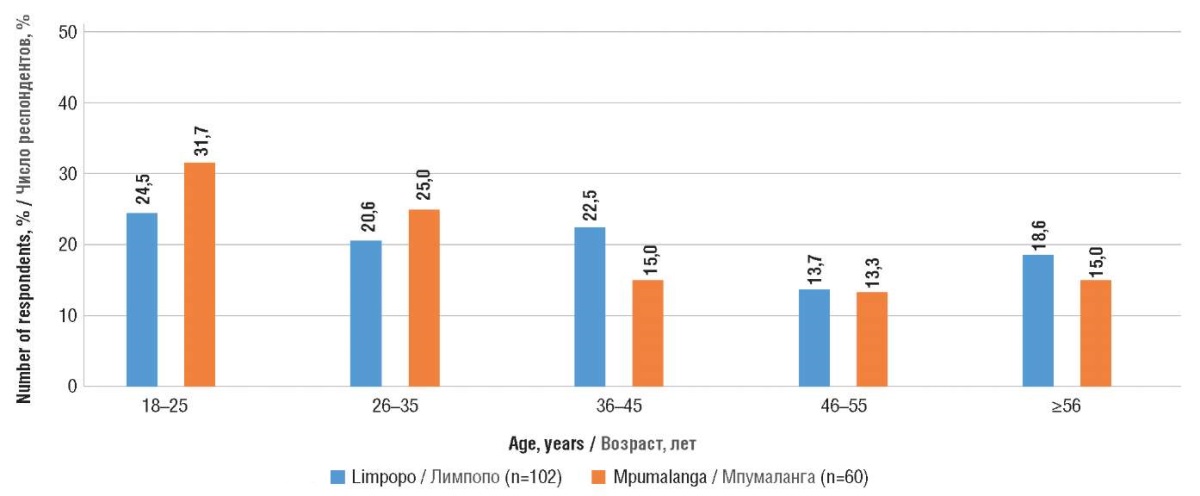

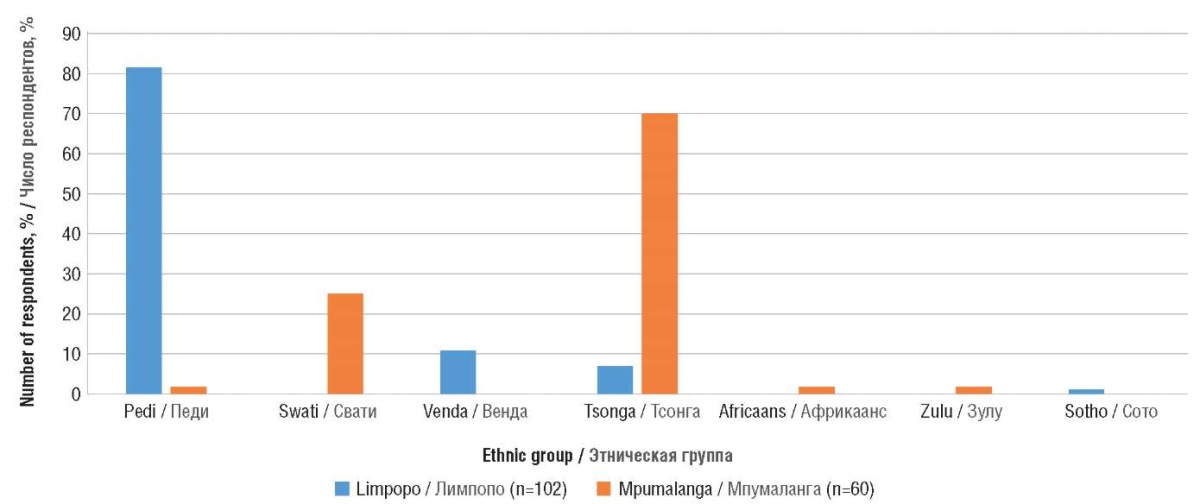

This current study included more males than females (60.8% in Limpopo, 51.7% in Mpumalanga) (Fig. 1). In Limpopo, most respondents (24.5%) were within the 18–25 age range, 22.5% constituted respondents between 36 and 45, and only 18% were above 56 years of age. In Mpumalanga, 31.7% constituted respondents aged 18–25, whereas 25% fell within the 26–35 age range. Only 15% were 56 years old and above (Fig. 2). Regarding ethnic groups, 81.4% were Pedi speaking and 10.8% were Venda in Limpopo, 70% were Tsonga and 25% were Swati in Mpumalanga (Fig. 3).

Figure 1. Gender distribution of respondents

Рисунок 1. Гендерное распределение респондентов

Figure 2. Age range of respondents

Рисунок 2. Возрастной диапазон респондентов

Figure 3. Ethnic groups of respondents

Рисунок 3. Этнические группы респондентов

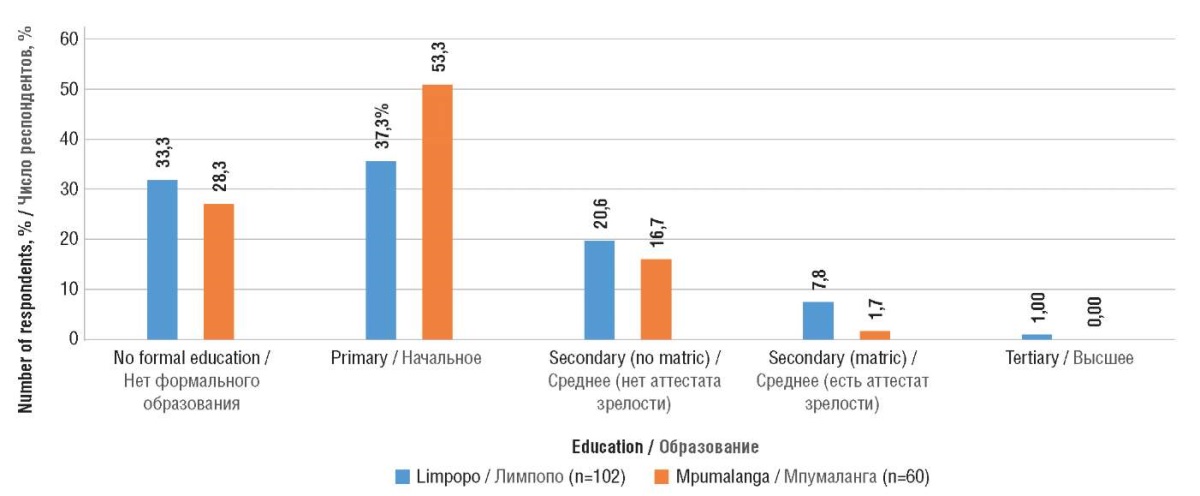

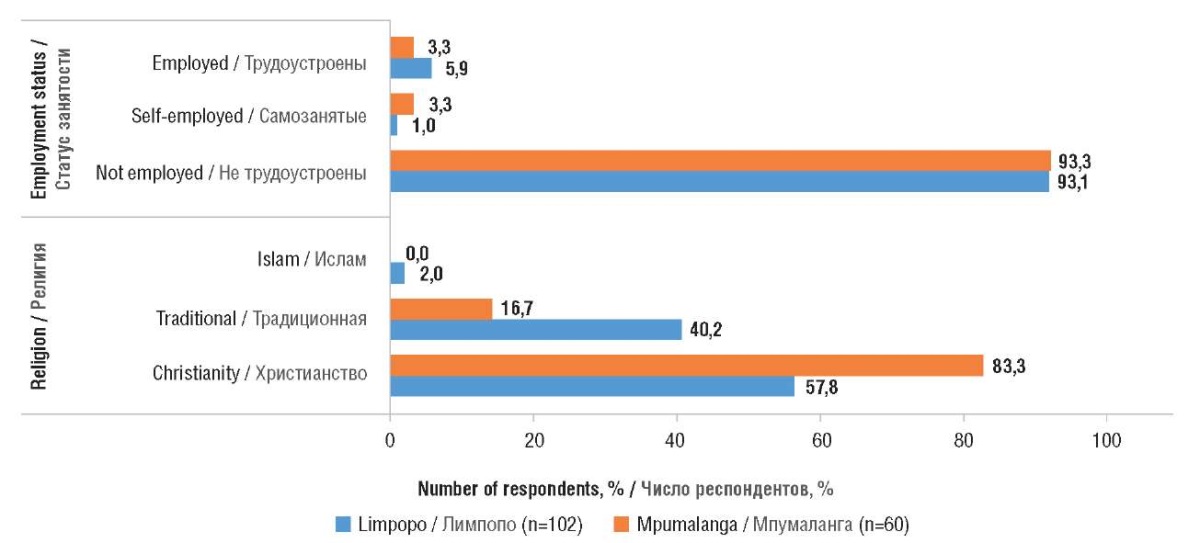

Many respondents never furthered their studies past primary level (37.3% in Limpopo and 53.3% in Mpumalanga), whereas 33.3% in Limpopo and 28.3% in Mpumalanga had no education (Fig. 4). In Limpopo, 93.1% of respondents and 93.3% in Mpumalanga were unemployed (Fig. 5). The majority of participants in the study were adherents of the Christian faith.

Figure 4. Level of respondents’ education

Рисунок 4. Уровень образования респондентов

Figure 5. Employment status and religion of respondents

Рисунок 5. Статус занятости и религиозная принадлежность респондентов

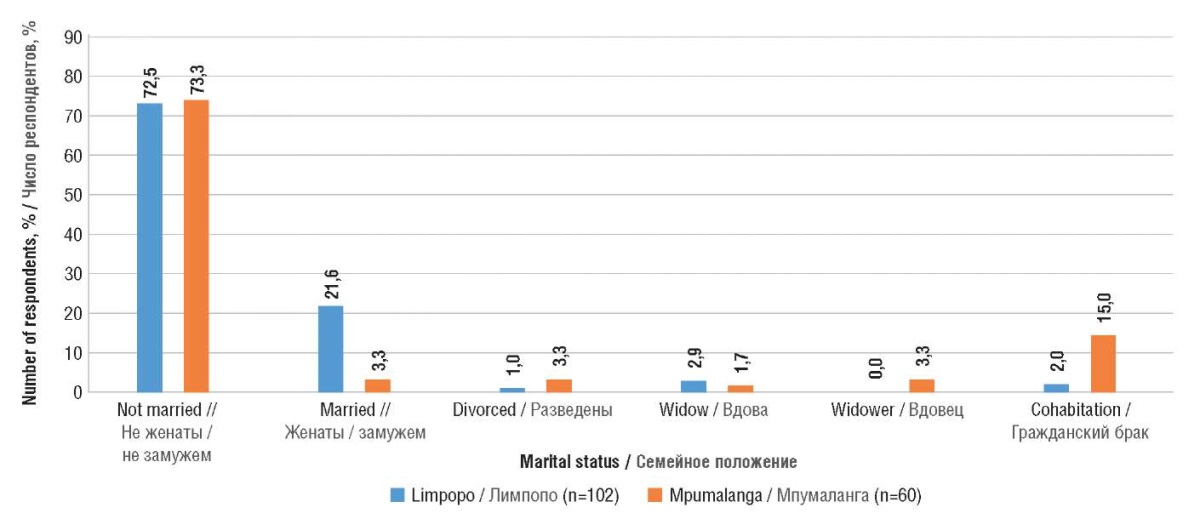

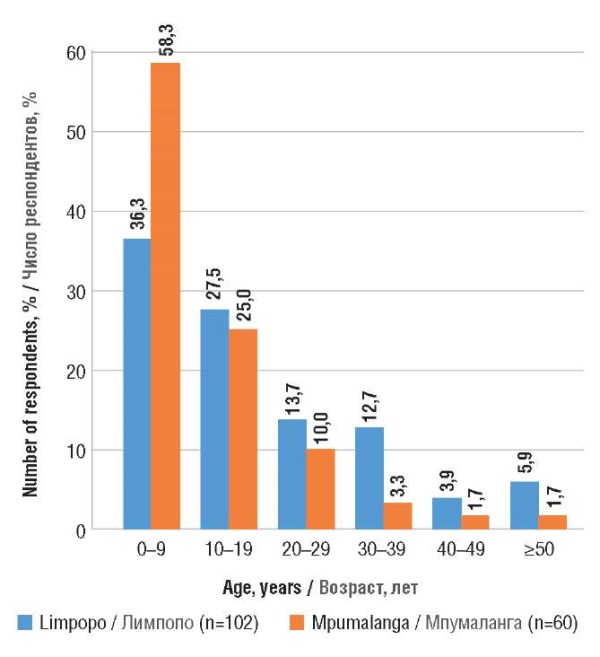

The marital status of the responders and distribution by age when they first were diagnosed with epilepsy are shown in Figures 6, 7.

Figure 6. Marital status of respondents

Рисунок 6. Семейное положение респондентов

Figure 7. Age when the responders were first diagnosed with epilepsy

Рисунок 7. Возраст постановки диагноза эпилепсии

Knowledge on epilepsy / Знания об эпилепсии

Of the nine questions about epilepsy knowledge, most respondents answered eight correctly, as illustrated in Table 1. In this scenario, 64.2% of respondents agreed that PLWE can lead a normal life, and Cramer's V value of –0.006 indicates a consensus across both provinces on this belief. However, the negative and minimal value of Cramer's V points to a very slight variation in the intensity or conviction of this belief between the two provinces. Essentially, while there is widespread agreement on the capability of PLWE to live normally, the strength of this agreement varies marginally between the two provinces. In this study, 56.2% of participants concurred that PLWE should be allowed to attend regular schools. Conversely, 53.1% of respondents believed that PLWE should attend special schools. The significant Chi-square value (χ²=4.018, p<0.001) alongside a Cramer's V of –0.157 indicates a meaningful association between the respondents' opinions and their provincial location. This suggests that attitudes towards the need for special education for PLWE vary notably between provinces, as evidenced by the negative Cramer's V value, which highlights a divergence in perspectives across different areas.

Table 1. Assessment of knowledge held by people living with epilepsy, n %

Таблица 1. Результаты оценки знаний у людей с диагнозом эпилепсии, n %

|

Question / Вопрос |

Answer / Ответ |

Limpopo / Лимпопо |

Mpumalanga / Мпумаланга |

Total / Всего |

χ² |

p |

Cramer's V / V Крамера |

|

People living with epilepsy can live a normal life / Люди с диагнозом эпилепсии могут жить нормальной жизнью |

Agree / Согласен |

63 (61.8) |

41 (68.3) |

104 (64.2) |

0.709 |

<0.001 |

–0.066 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

39 (38.2) |

19 (31.7%) |

58 (35.8) |

||||

|

Epilepsy is just like any other chronic condition / Эпилепсия не отличается от других хронических заболеваний |

Agree / Согласен |

61 (59.8) |

42 (70.0) |

103 (63.6) |

1.696 |

<0.001 |

–0.102 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

41 (40.2) |

18 (30.0) |

59 (36.4) |

||||

|

Epilepsy can be controlled by Western medicine / Эпилепсию можно контролировать с помощью западной медицины |

Agree / Согласен |

80 (78.4) |

48 (80.0) |

128 (79.0) |

0.056 |

<0.001 |

–0.019 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

22 (21.6) |

12 (20.0) |

34 (21.0) |

||||

|

Epilepsy can be controlled by traditional indigenous medicine / Эпилепсию можно контролировать с помощью традиционной народной медицины |

Agree / Согласен |

33 (32.4) |

16 (26.7) |

49 (30.2) |

1.033 |

<0.001 |

–0.080 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

69 (67.6) |

44 (73.3) |

113 (69.8) |

||||

|

Epilepsy can be completely cured by traditional indigenous medicine / Эпилепсию можно полностью вылечить методами традиционной народной медицины |

Agree / Согласен |

33 (32.4) |

16 (26.7) |

49 (30.2) |

0.579 |

<0.001 |

0.060 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

69 (67.6) |

44 (73.3) |

113 (69.8) |

||||

|

Epilepsy can be completely cured by prayer / Эпилепсию можно полностью вылечить молитвами |

Agree / Согласен |

29 (28.4) |

13 (21.7) |

42 (25.9) |

0.900 |

<0.001 |

0.075 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

73 (71.6) |

47 (78.3) |

120 (74.1) |

||||

|

A person living with epilepsy should attend a special school / Люди с диагнозом эпилепсии должны посещать специальную школу |

Agree / Согласен |

48 (47.1) |

38 (63.3) |

86 (53.1) |

4.018 |

<0.001 |

–0.157 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

54 (52.9) |

22 (36.7) |

76 (46.9) |

||||

|

A person living with epilepsy should attend normal school / Люди с диагнозом эпилепсии должны посещать обычную школу |

Agree / Согласен |

63 (61.8) |

28 (46.7) |

91 (56.2) |

3.498 |

<0.001 |

0.147 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

39 (38.2) |

32 (53.3) |

71 (43.8) |

||||

|

I was spoken to about what epilepsy is, its causes and management / Со мной проведена беседа по основам эпилепсии, ее причинам и лечению |

Agree / Согласен |

71 (69.6) |

37 (61.7) |

108 (66.7) |

1.072 |

<0.001 |

0.081 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

31 (30.4) |

23 (38.3) |

54 (33.3) |

In addition, 69.8% did not agree that epilepsy could be entirely cured by traditional medicine, and 79% agreed when asked if epilepsy can be controlled by Western medicine. The data indicates that a significant majority of the respondents, 74.1%, expressed the belief that prayer cannot wholly cure epilepsy. This view is supported by a Chi-square value of 0.900 and a highly significant p-value (p<0.001). Although negative, the Cramer's V value of –0.075 suggests a slight association between the respondents' opinions and their demographic or provincial grouping. In essence, while the belief that prayer cannot cure epilepsy is widely held, the strength of this belief shows only a minimal variation across different respondent groups.

Psychosocial impact and experiences of living with epilepsy / Психосоциальное воздействие и опыт жизни с эпилепсией

The respondents in this study showed that their life experiences of living with epilepsy also had some psychosocial impact, which influenced their overall well-being (Table 2). When asked if they felt depressed by their condition, 50.0% said they always felt depressed, and 29.6% felt depressed sometimes. The analysis revealed a notable association between the provinces and the experience of depression attributed to epilepsy, as evidenced by a Chi-square value of 23.993 and a highly significant p-value (p<0.001). Furthermore, the Cramer’s V value of 0.385 indicates a substantial association, suggesting distinct variations in the emotional impact of epilepsy across the two provinces. Specifically, this finding implies that patients from Mpumalanga tend to report depressive feelings more frequently about their epilepsy condition compared to those from other areas. This highlights a considerable geographical disparity in the psychological effects of epilepsy.

Table 2. Psychosocial impact and expectations of people living with epilepsy, n %

Таблица 2. Психосоциальное влияние и ожидания людей с диагнозом эпилепсии, n %

|

Question / Вопрос |

Answer / Ответ |

Limpopo / Лимпопо |

Mpumalanga / Мпумаланга |

Total / Всего |

χ² |

p |

Cramer's V / V Крамера |

|

I’m not allowed to be near fire or heater / Мне нельзя находиться рядом с огнем или обогревателем |

Never / Никогда |

32 (31.4) |

5 (8.3) |

37 (22.8) |

20.968 |

<0,001 |

0.360 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

22 (21.6) |

5 (8.3) |

27 (16.7) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

48 (47.1) |

50 (83.3) |

98 (60.5) |

||||

|

I feel depressed because of my condition / Я ощущаю депрессию из-за своего состояния |

Never / Никогда |

26 (25.5) |

7 (11.7) |

33 (20.4) |

23.993 |

<0.001 |

0.385 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

40 (39.2) |

8 (13.3) |

48 (29.6) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

36 (35.3) |

45 (75.0) |

81 (50.0) |

||||

|

I feel helpless for not being in control of this condition / Я чувствую беспомощность из-за невозможности контролировать данное состояние |

Never / Никогда |

22 (21.6) |

6 (10.0) |

28 (17.3) |

12.999 |

<0.001 |

0.385 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

48 (47.1) |

18 (30.0) |

66 (40.7) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

32 (31.4) |

36 (60.0) |

68 (42.0) |

||||

|

I feel shameful after an epileptic seizure / Я испытываю чувство стыда после эпилептического припадка |

Never / Никогда |

22 (21.6) |

12 (20.0) |

34 (21.0) |

20.765 |

<0.001 |

0.358 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

45 (44.1) |

8 (13.3) |

53 (32.7) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

34 (33.3) |

40 (66.7) |

74 (45.7) |

||||

|

I feel cursed because I am living with epilepsy / Я испытываю чувство проклятости из-за диагноза эпилепсии |

Never / Никогда |

25 (24.5) |

22 (36.7) |

47 (29.0) |

9.300 |

<0.001 |

0.240 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

54 (52.9) |

17 (28.3) |

71 (43.8) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

23 (22.5) |

21 (35.0) |

44 (27.2) |

||||

|

I try to keep my condition secret / Я стараюсь скрывать свою болезнь |

Never / Никогда |

53 (52.0) |

25 (41.7) |

78 (48.1) |

3.143 |

<0.001 |

0.139 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

33 (32.4) |

19 (31.7) |

52 (32.1) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

16 (15.7) |

16 (26.7) |

32 (19.8) |

||||

|

I feel emotionally stressed / Я ощущаю эмоциональное напряжение |

Never / Никогда |

22 (21.6) |

12 (20.0) |

34 (21.0) |

12.198 |

0.001 |

0.274 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

47 (46.1) |

13 (21.7) |

60 (37.0) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

33 (32.4) |

35 (58.3) |

68 (42.0) |

||||

|

I feel that my family is overprotecting me / Я ощущаю гиперопеку со стороны своей семьи |

Never / Никогда |

14 (13.7) |

11 (18.3) |

25 (15.4) |

8.257 |

<0.001 |

0.226 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

18 (17.6) |

21 (35.0) |

39 (24.1) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

70 (68.6) |

28 (46.7) |

98 (60.5) |

||||

|

I am forced to medicate in a way I don’t condone / Меня заставляют лечиться способом, который я не одобряю |

Never / Никогда |

60 (60.8) |

30 (50.0) |

92 (56.8) |

4.341 |

<0.001 |

0.164 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

23 (22.5) |

13 (21.7) |

36 (22.2) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

17 (16.7) |

17 (28.3) |

35 (21.0) |

||||

|

I feel that my family does not care about my condition / Я чувствую безразличие к моему состоянию со стороны семьи |

Never / Никогда |

61 (59.8) |

36 (60.0) |

97 (59.9) |

0.483 |

<0.001 |

0.055 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

22 (21.6) |

15 (25.0) |

37 (22.8) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

19 (18.6) |

9 (15.0) |

28 (17.3) |

||||

|

I have been subject to bullying and/or abuse because of epilepsy // Я подвергаюсь травле и/или жестокому обращению из-за эпилепсии |

Never / Никогда |

44 (43.1) |

11 (18.3) |

55 (34.0) |

27.959 |

<0.001 |

0.415 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

37 (36.3) |

12 (20.0) |

49 (30.2) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

21 (20.6) |

37 (61.7) |

58 (35.8) |

||||

|

I have a supportive family and friends / Меня поддерживают семья и друзья |

Never / Никогда |

9 (8.8) |

7 (11.7) |

16 (9.9) |

0.774 |

<0.001 |

0.069 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

20 (19.6) |

9 (15.0) |

29 (17.9) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

73 (71.6) |

44 (73.3) |

117 (72.2) |

||||

|

I am happy / Я счастлив(а) |

Never / Никогда |

12 (11.8) |

24 (40.0) |

36 (22.2) |

17.437 |

<0.001 |

0.328 |

|

Sometimes / Иногда |

39 (38.2) |

16 (26.7) |

55 (34.0) |

||||

|

Always / Всегда |

51 (50.0) |

20 (33.3) |

71 (43.8) |

||||

|

A person living with epilepsy is always dependent / Человек с диагнозом эпилепсии всегда зависим |

Agree / Согласен |

58 (56.9) |

55 (91.7) |

113 (69.8) |

21.689 |

<0.000 |

–0.366 |

|

Disagree /Не согласен |

44 (43.1) |

5 (8.3) |

49 (30.2) |

||||

|

People do not feel comfortable with me because of my epilepsy / Окружающим некомфортно со мной из-за моей эпилепсии |

Agree / Согласен |

49 (48.0) |

32 (54.2) |

81 (50.3) |

0.574 |

<0.001 |

–0.060 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

53 (52.0) |

27 (45.8) |

80 (49.7) |

||||

|

People avoid interacting with me because of my epilepsy / Люди избегают общения со мной из-за моей эпилепсии |

Agree / Согласен |

51 (50.0) |

26 (43.3) |

77 (47.5) |

0.673 |

<0.001 |

0.064 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

51 (50.0) |

34 (56.7) |

85 (52.5) |

||||

|

I was never married because of epilepsy / Я не вступаю в брак из-за эпилепсии |

Agree / Согласен |

41 (40.6) |

33 (55.0) |

74 (46.0) |

3.145 |

<0.001 |

–0.140 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

60 (59.4) |

27 (45.0) |

87 (54.0) |

||||

|

I lost my job because of epilepsy / Я потерял(а) работу из-за эпилепсии |

Agree / Согласен |

44 (43.6) |

29 (48.3) |

73 (45.3) |

0.345 |

<0.001 |

–0.046 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

57 (56.4) |

31 (51.7) |

88 (54.7) |

||||

|

I dropped out of school because of epilepsy / Я бросил(а) школу из-за эпилепсии |

Agree / Согласен |

49 (48.0) |

44 (73.3) |

93 (57.4) |

9.885 |

<0.001 |

–0.247 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

53 (52.0) |

16 (26.7) |

69 (42.6) |

||||

|

I am unable to build lasting social relationships because of epilepsy / Я не могу строить длительные социальные отношения из-за эпилепсии |

Agree / Согласен |

50 (49.0) |

36 (60.0) |

86 (53.1) |

1.829 |

<0.001 |

–0.106 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

52 (51.0) |

24 (40.0) |

76 (46.9) |

||||

|

People around me started treating me differently once they knew I was living with epilepsy / Окружающие изменили свое отношение ко мне, узнав, что у меня эпилепсия |

Agree / Согласен |

42 (41.2) |

26 (43.3) |

68 (42.0) |

0.072 |

<0.001 |

–0.021 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

60 (58.8) |

34 (56.7) |

94 (58.0) |

||||

|

I am able to talk to others about epilepsy sufficiently / Я могу свободно говорить с окружающими об эпилепсии |

Agree / Согласен |

70 (68.6) |

35 (58.3) |

105 (64.8) |

1.755 |

<0.001 |

0.104 |

|

Disagree / Не согласен |

32 (31.4) |

25 (41.7) |

57 (35.2) |

The findings further indicated that a minority of 21.0% reported never experiencing shame following an epileptic seizure. In contrast, a substantial proportion, 45.7%, consistently felt shameful after such events. The statistical analysis demonstrates a relatively strong association, including a Chi-square value of 9.300 and a p-value significantly less than 0.001, accompanied by a Cramer's V of 0.240. This suggests notable differences in emotional responses to epileptic seizures across provinces, with individuals in Mpumalanga more likely to report feelings of shame in the aftermath of a seizure. This finding underscores the varying emotional impacts of epilepsy in different geographical areas. Most respondents indicated that they occasionally (43.8%) feel cursed due to living with epilepsy. Additionally, a significant portion (42.0%), as highlighted by a Chi-square value of 12.198 and a p-value of 0.001, along with a Cramer's V of 0.274, consistently experience emotional stress. These statistics suggest moderate differences in the levels of emotional stress associated with epilepsy between the two provinces. This variation points to a divergence in the psychological impact of epilepsy, with a notable proportion of individuals experiencing feelings of being cursed or undergoing persistent emotional stress.

From both provinces, most respondents (35.8%) stated that they had been bullied or abused because of epilepsy. About 50.3% of respondents felt that people weren’t comfortable with them because of the disease. However, 52.5% argued that epilepsy did not influence people to avoid interacting with them. Moreover, only 46.0% stated that they were never married because of epilepsy, 57.4% dropped out of school, and 60.0% in Mpumalanga agreed that they could not build lasting relationships because of the disease, whereas 51% from Limpopo did not agree with this.

Regarding epilepsy disclosure, the greater majority (64.8%) said that they were able to speak to others about epilepsy sufficiently, and an overall of 48.1% said they never tried to keep their condition secret.

DISCUSSION / ОБСУЖДЕНИЕ

The data from this study allude to the fact that this condition may impact the quality of life for PLWE. We also found that a greater majority of respondents agreed that a person living with epilepsy could live a normal life, but a sizable number disagreed that this was possible [21–23]. Some studies suggest that traditional and spiritual intervention are of first preference for epilepsy treatment or management and is seen as more effective [24][25]. This study's respondents prefer Western medication as a traditional and spiritual means of healing, irrespective of the majority being believers. This may be attributed to personal experiences of having epileptic seizures and taking these different forms of medication. However, they found that taking Western medication manages seizures better.

In this study, a majority of the respondents were diagnosed with epilepsy in their childhood, and this may have resulted in some school bullying, difficulties making friends and social connections, and building a secure sense of self [26–28]. These social factors coupled together with early onset, an inability to cope with the illness, potential difficulties for parents/caregivers (not being able to oversee the child or having to leave work often to fetch the child from school), and teachers (untrained on epilepsy-related care) may be major contributors to the high levels of school dropout [10][22][29–31].

This notion may be supported by the study findings that showed little difference between PLWE, who believed that they should attend special school, and those who think they should attend normal school. On the other hand, dropping out of school due to epilepsy can lead to a lack of employment opportunities, making PLWE financially dependent on others and exacerbating their social challenges. For individuals of age, unemployment, financial lack, and thinking of epilepsy as a burden may be the cause of why they were never married. In addition to L. Makhado et al. [11] findings, the present study found that a significant proportion of PLWE reported never marrying; however, they mostly do not attribute it to epilepsy. It is essential to note that not all PLWE hold this belief, as some respondents in our study did not agree that epilepsy should hamper marriage.

The study found that PLWE also faces negative psychological challenges due to living with epilepsy and the psychosocial challenges they experience. We found that a majority of the respondents reported feeling depressed, helpless, and shameful after having an epileptic seizure. These negative emotions are often associated with epilepsy and can significantly impact the mental health and well-being of PLWE [11][22][32–34]. The negative impacts of epilepsy on an individual’s psychosocial way of life may interrupt normal life functioning [35]. In addition, a just above-average percentage of participants stated that someone had spoken to them about epilepsy. This may suggest that PLWE are not adequately educated and empowered with survival tools and techniques, especially on how to live a successful, normal life.

The findings of this study suggest that epilepsy can significantly impact the quality of life of PLWE, affecting their social, emotional, and psychological well-being. The study highlights the need for healthcare providers to provide intentional education about epilepsy to PLWE and for the provision of local epilepsy support groups to help them cope with the psychosocial challenges associated with the condition. A preference for Western medication among PLWE was also revealed, despite some studies suggesting traditional and spiritual interventions as the first preference for epilepsy treatment. We emphasize the importance of providing PLWE with adequate tools and techniques to help them live a successful, normal life, especially considering the negative psychosocial impacts of epilepsy. The study recommends measures to prevent school bullying and support for caregivers, teachers, and PLWE to avoid school dropout and financial dependence.

Study limitations / Ограничения исследования

One limitation of the study was using a quantitative methodology, using different scales to measure the same variable. In addition, although the main focus was not to conduct a strict psychiatric/psychological assessment, the study would have benefited from a vigorous psychometric assessment tool to explain the psychological position of PLWE in depth.

Acknowledgements / Благодарности

The researchers want to acknowledge Mpumalanga and Limpopo home-based carers for assisting during data collection and GERP project students for capturing all recorded data.

CONCLUSION / ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

This study aimed to investigate the knowledge and psychosocial impact of epilepsy among PLWE. The findings showed that while PLWE have a good understanding of epilepsy as a medical condition, they may not fully comprehend its impact on their daily lives. The study also highlighted the significant psychosocial impact of epilepsy on PLWE, including depression, difficulties forming and maintaining social connections, and a lack of marital experience.

Future studies may benefit from a qualitative approach to allow PLWE to express their experiences in their own words. Additionally, it may be helpful for researchers to explore PLWE's coping mechanisms for dealing with their condition. It is recommended that healthcare providers should provide intentional education about epilepsy to PLWE and that PLWE should have access to local epilepsy support groups. The researchers also suggest that PLWE should be referred for psychological services to help them cope with the psychosocial challenges associated with epilepsy.

References

1. Beghi E. The epidemiology of epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology. 2020; 54 (2): 185–91. https://doi.org/10.1159/000503831.

2. Hu Y., Shan Y., Du Q., et al. Gender and socioeconomic disparities in global burden of epilepsy: an analysis of time trends from 1990 to 2017. Front Neurol. 2021; 12: 643450. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.643450.

3. Jahan S., Nowsheen F., Antik M.M., et al. AI-based epileptic seizure detection and prediction in internet of healthcare things: a systematic review. IEEE Xplore. 2023; 11: 30690–725. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3251105.

4. Shihata S.S., Abdullah T.S., Alfaidi A.M., et al. Knowledge, perception and attitudes toward epilepsy among medical students at King Abdulaziz University. SAGE Open Med. 2021; 9: 2050312121991248. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312121991248.

5. Ogundare T., Adebowale T.O., Borba C.P., Henderson D.C. Correlates of depression and quality of life among patients with epilepsy in Nigeria. Epilepsy Res. 2020; 164: 106344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106344.

6. Tombini M., Assenza G., Quintiliani L., et al. Epilepsy and quality of life: what does really matter? Neurol Sci. 2021: 42 (9): 3757–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04990-6.

7. Muhigwa A., Preux P.M., Gerard D., et al. Comorbidities of epilepsy in low and middle-income countries: systematic review and metaanalysis. Sci Rep. 2020; 10 (1): 9015. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65768-6.

8. Yogarajah M., Mula M. Social cognition, psychiatric comorbidities, and quality of life in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2019; 100 (Pt. B): 106321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.05.017.

9. Mikulecká A., Druga R., Stuchlík A., et al. Comorbidities of early-onset temporal epilepsy: cognitive, social, emotional, and morphologic dimensions. Exp Neurol. 2019; 320: 113005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113005.

10. Syvertsen M., Vasantharajan S., Moth T., et al. Predictors of high school dropout, anxiety, and depression in genetic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsia Open. 2020; 5 (4): 611–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.12434.

11. Makhado L., Maphula A., Makhado T.G., Musekwa O.P. Perspective chapter: practical approaches to enhance successful lives among people living with epilepsy. In: Mothiba T.M., Mutshatshi T.E., Ramavhoya I. (Eds.) Health and educational success – recent perspectives. IntechOpen; 2023: 258 pp.

12. Musekwa O.P., Makhado L., Maphula A., Mabunda J.T. How much do we know? Assessing public knowledge, awareness, impact, and awareness guidelines for epilepsy: a systematic review. Open Public Health J. 2020; 13 (1): 794–807. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874944502013010794.

13. Giuliano L., Cicero C.E., Padilla S., et al. Knowledge, stigma, and quality of life in epilepsy: results before and after a community-based epilepsy awareness program in rural Bolivia. Epilepsy Behav. 2019; 92: 90–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.11.036.

14. Alaqeel A., Alebdi F., Sabbagh A.J. Epilepsy: what do healthcare professionals in Riyadh know? Epilepsy Behav. 2013; 29 (1): 234–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.07.009.

15. Samanta D., Hoyt M.L., Perry M.S. Healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitude, and perception of epilepsy surgery: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2021; 122: 108199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

16. yebeh.2021.108199.

17. Chomba E.N., Haworth A., Atadzhanov M., et al. Zambian health care workers’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2007; 10 (1): 111–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.08.012.

18. Kabel A.M., Algethami S.A., Algethami B.S., et al. Knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes of students of health-related science colleges towards epilepsy in Taif, Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020; 9 (5): 2394–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_299_20.

19. Tashakori-Miyanroudi M., Souresrafil A., Hashemi P., et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress in patients with epilepsy during COVID-19: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2021; 125: 108410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108410.

20. Scott A.J., Sharpe L., Loomes M., Gandy M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of anxiety and depression in youth with epilepsy. J Pediatr Psychol. 2020; 45 (2): 133–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsz099.

21. Viswanathan S., Abdul Khalid R. Socioeconomic and psychological impact of quality of life in Malaysian patients with epilepsy. Neurol Asia. 2004; 9 (Suppl. 1): 141.

22. Riechmann J., Willems L.M., Boor R., et al. Quality of life and correlating factors in children, adolescents with epilepsy, and their caregivers: a cross-sectional multicenter study from Germany. Seizure. 2019; 69: 92–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2019.03.016.

23. Minwuyelet F., Mulugeta H., Tsegaye D., et al. Quality of life and associated factors among patients with epilepsy at specialized hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia; 2019. PLoS One. 2022; 17 (1): e0262814. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262814.

24. Thara D.K., PremaSudha B.G., Xiong F. Epileptic seizure detection and prediction using stacked bidirectional long short term memory. Pattern Recognit Let. 2019; 128: 529–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2019.10.034.

25. Anand P., Othon G.C., Sakadi F., et al. Epilepsy and traditional healers in the Republic of Guinea: a mixed methods study. Epilepsy Behav. 2019; 92: 276–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.01.017.

26. Mesraoua B., Kissani N., Deleu D., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for epilepsy treatment in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Epilepsy Res. 2021; 170: 106538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106538.

27. Gauffin H., Landtblom A.M., Räty L. Self-esteem and sense of coherence in young people with uncomplicated epilepsy: a 5-year follow-up. Epilepsy Behav. 2010; 17 (4): 520–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.01.167.

28. Räty L.K., Söderfeldt B.A., Larsson B.M. Daily life in epilepsy: patients’ experiences described by emotions. Epilepsy Behav. 2007; 10 (3): 389–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.02.003.

29. Henning O., Landmark C.J., Henning D., et al. Challenges in epilepsy – the perspective of Norwegian epilepsy patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2019; 140 (1): 40–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.13098.

30. Makhado T.G., Lebese R.T., Maputle M.S. Perceptions of teachers regarding the inclusion of epilepsy education in life skills for primary learners and teachers in Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces (South Africa). Epilepsia i paroksizmalʹnye sostoania / Epilepsy and Paroxysmal Conditions. 2022; 14 (4): 334–43. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2022.132.

31. Camfield P.R., Andrade D., Camfield C.S., et al. How can transition to adult care be best orchestrated for adolescents with epilepsy? Epilepsy Behav. 2019; 93: 138–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.12.015.

32. Musekwa O.P., Makhado L., Maphula A. Caregivers’ and family members’ knowledge attitudes and practices (KAP) towards epilepsy in rural Limpopo and Mpumalanga, South Africa. Int J Environment Res Public Health. 2023; 20 (6): 5222. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065222.

33. Yang Y., Yang M., Shi Q., et al. Risk factors for depression in patients with epilepsy: a meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 2020; 106: 107030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107030.

34. Ali Arazeem A., Tahirah Adedolapo I., Joseph Alabi O. Shame, stigma, and social exclusion: the lived experiences of epileptic patients in a health facility in Ilorin, Nigeria. Glob Public Health. 2022: 17 (12): 3839–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2022.2092174.

35. Bauer P.R., Bronnec M.L., Schulze-Bonhage A., et al. Seizures as a struggle between life and death: an existential approach to the psychosocial impact of seizures in candidates for epilepsy surgery. Psychopathology. 2023 Mar 16: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1159/000528924.

36. Epilepsy Foundation. Epilepsy: impact on the life of the child. Available at: https://www.epilepsy.com/stories/epilepsy-impact-life-child (accessed 10.08.2023).

About the Authors

O. P. MusekwaSouth Africa

Ofhani Prudance Musekwa – Student, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Health Science

University Rd, Thohoyandou 0950, South Africa

L. Makhado

Russian Federation

Lufuno Makhado – Lecturer, Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Science

University Rd, Thohoyandou 0950, South Africa

WoS ResearcherID: I-1586-2016; Scopus Author ID: 56224434100

Review

For citations:

Musekwa O.P., Makhado L. Living with epilepsy: patient knowledge and psychosocial impact. Epilepsy and paroxysmal conditions. 2024;16(1):33-44. https://doi.org/10.17749/2077-8333/epi.par.con.2024.166

JATS XML

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.